Dylan Context

Anyone who attended the Never Ending Tour in 1988 knew that Dylan was back. In 1989 he announced the comeback to a wider audience with Oh Mercy, released a month after his Riverbend ’89 concert. Not only was this Dylan’s strongest album of original songs in years, but in the fullness of time it holds up as one of the best of his entire career. If you’re as a big a fan of the album as I am, you might enjoy my earlier piece called “Creole Trilogy,” tracing connections between three 1989 albums produced by Daniel Lanois in New Orleans: Oh Mercy, The Neville Brothers’ Yellow Moon, and Lanois’s own Acadie. Typing out those titles makes me want to go back and listen to them all over again, just as I have been reconnecting with their close cousin, Robbie Robertson, co-produced by Robertson and Lanois in 1987. RIP Robbie.

Dylan devotes the longest chapter of Chronicles to Oh Mercy, first contextualizing it within his 1980s malaise, and then chronicling a series of creative disputes and personality conflicts with producer Daniel Lanois while making the record in New Orleans. Though the production was contentious from the start, the quality of Dylan’s new compositions made it worth the effort to get them right in the studio. As he notes in Chronicles, the resulting album may not have been what either Dylan or Lanois set out to make, but the success of their collaboration was ultimately undeniable. He acknowledges that “we were kind of kindred spirits” (221) and “There’s something magical about this record” (220). Dylan’s songwriting is superb and his vocals are haunting, but Lanois’s atmospheric soundscape is primarily responsible for making Oh Mercy sonically distinct from any other Dylan album.

The duo fought like Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot in the captain’s tower of “Desolation Row,” but what they created together in 1989 was worth the struggle. Dylan recognizes as much in Chronicles and gives major credit to Lanois: “He slept music. He ate it. He lived it. A lot of what he did was pure genius. He steered this record with deft turns and jerks, but he did it. He stood in the bell tower, scanning the alleys and rooftops. My limited vision didn’t permit me to see all around the thing” (220).

Meanwhile, Dylan was earning acclaim for a much more pleasant recording experience with some famous pals who called themselves The Traveling Wilburys. In May 1988, George Harrison was working on a song for the B-side of his single “This Is Love” from the album Cloud Nine produced by Jeff Lynne. The former Beatle and the ex-ELO frontman happened to be hanging around Dylan’s studio, and they roped in Roy Orbison and Tom Petty for an impromptu collaboration. The resulting song “Handle with Care” was so good, and the creative process so enjoyable, that the gang decided to keep the momentum going.

Dylan was about to begin his new tour in June 1988, so the supergroup’s window of opportunity was brief. They were on fire with sudden inspiration, and in less than two weeks managed to record an album’s worth of new songs. The Traveling Wilburys Vol. 1 was released in October 1988. Joy and camaraderie shine through in the final product. It’s a wonderful album, with Dylan featured on the standout tracks “Dirty World,” “Tweeter and the Monkey Man,” and “Congratulations.” The Traveling Wilburys Vol. 1 was holding steady on the charts and still receiving massive airplay when he returned to touring in 1989.

In 1988 Dylan played 71 concerts, which may sound like a lot, until you consider that it’s actually the fewest number of shows for any year of the NET. In 1989 he played exactly 100 shows and would keep up that pace for three decades. Beginning in June 1989, he was joined by Tony Garnier, who filled in for Kenny Aaronson during an illness and soon replaced him permanently on bass. Garnier previously played in the band Asleep at the Wheel, and he sometimes sat in with G. E. Smith’s house band on Saturday Night Live. Dylan clearly liked what he heard. Garnier has remained a fixture in the band ever since, playing over 3,000 shows alongside Dylan, by far more than any other musician.

In Ray Padgett’s Pledging My Time: Conversations with Bob Dylan Band Members, Ray Benson, co-founder of Asleep at the Wheel, describes the bassist’s indispensable role in Dylan’s band: “Tony Garnier has been an addition to Bob that has been immeasurably positive. Just look at his track record, been with Bob for 30-some-odd years. I call him the Bob Whisperer. Bob listens to him in terms of musical things. It’s one of the reasons I think that Bob is out there doing new things every day. Because it ain’t easy. What Tony does is not easy at all” (385). The Dylan Whisperer’s first of many NET appearances in Cincinnati came on August 10, 1989.

On a personal note, the 1989 summer tour is dear to me because that’s when I saw my first Dylan concert. Ten days after the band played Riverbend, they headed south to Starwood Amphitheatre outside of Nashville, Tennessee, on August 20, 1989.

I was a sophomore at the University of Tennessee and drove three hours from Knoxville to see the show. It rained all day and night. I don’t know how many tickets were sold, but the lousy weather scared away many fans from the outdoor venue. Starwood officials closed off the saturated hillside, a hazardous mudslide waiting to happen, and let all ticket holders sit in the covered pavilion. This meant that I ended up closer to the stage than expected for my first live glimpse of Dylan. When he took the stage, I felt the intoxicating surge of adrenaline-fueled amazement that I’ve continued to feel over the years at the start of every concert: “I can’t believe I’m actually in the presence of Bob Fucking DYLAN!” To be honest, I don’t have many specific recollections about the performance that night. It’s more the magical aura surrounding the experience that stays with me.

Cincinnati Context

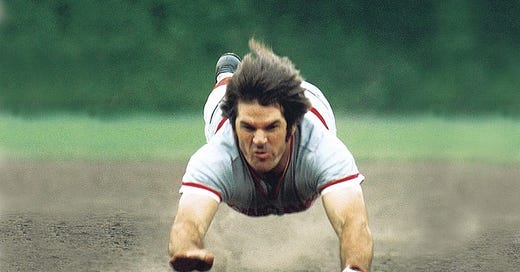

When Dylan returned to town in August 1989, the city was reeling from the Pete Rose scandal. A native of Cincinnati, Rose was a pillar of “the Big Red Machine” of the 1970s, one of the greatest baseball teams of all time. The Reds won back-to-back World Series titles (1975-76), with their all-star third-baseman batting leadoff and playing in every single regular season and playoff game during those championship years. Nicknamed “Charlie Hustle” for his aggressive style of play, he was the sparkplug igniting baseball’s most potent offense.

Rose joined the Philadelphia Phillies in 1979 and won another championship with them before making a triumphant return to the Reds in 1984 as player/manager of the team. On September 11, 1985, he became baseball’s “Hit King” by surpassing Ty Cobb’s seemingly unbreakable record for most career hits. He retired as a player in 1986 but stayed on as Reds manager. There was no bigger name in Cincinnati sports than Pete Rose, and he seemed a guaranteed lock for enshrinement in baseball’s Hall of Fame.

Then it all came crashing down. Troubling allegations emerged regarding Rose’s long-term gambling obsession, including charges that he bet on games he was involved in as player and manager. On the morning of Dylan’s Cincinnati concert, the Enquirer reported that the commissioner’s office had audiotapes of Rose placing bets with a bookie, which was not only illegal in Ohio but also explicitly forbidden by Major League Baseball. According to the Post, the FBI also had evidence of the embattled manager’s involvement in a tax evasion scheme. Rose vehemently denied the charges and swore that he never did anything to jeopardize his team’s success or alter the outcome of any games he played in or coached. Diehard local fans defended and supported their hometown hero, then and now. But he was pilloried in the national press, his reputation was in ruin, and his expulsion seemed imminent. Two weeks after Dylan’s concert, on August 24, 1989, Rose was officially banished from baseball, and the Hit King was permanently barred from entering the Hall of Fame.

Born a month after Pete Rose, Bob Dylan was moving in the opposite direction in 1989, soaring like a phoenix on the wings of the NET. His flight pattern brought him back to the same city and venue as the year before; but the concert he played at Riverbend ’89 differed markedly—and instructively—from the Riverbend ’88 show.

The Concert

When: August 10, 1989

Where: Riverbend Music Center in Anderson Township

Opener: Steve Earle & The Dukes

Band: Bob Dylan (vocals, guitar, and harmonica); Tony Garnier (bass); Christopher Parker (drums); G. E. Smith (guitar and backup vocals)

Setlist:

1. “Most Likely You Go Your Way (And I’ll Go Mine)

2. “Absolutely Sweet Marie”

3. “Ballad of Hollis Brown”

4. “Watching the River Flow”

5. “I Want You”

6. “You’re a Big Girl Now”

*

7. “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right”

8. “One Too Many Mornings”

9. “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll”

*

10. “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35”

11. “I’m in the Mood for Love”

12. “Silvio”

13. “I Shall Be Released”

14. “Like a Rolling Stone”

*

15. “Mr. Tambourine Man”

16. “All Along the Watchtower”

First Electric Set & Acoustic Set

After a set from opening act Steve Earle & The Dukes [which Cincinnati Post critic Larry Nager described as “Grits ’n’ Roses” (6C)], the main event opens with “Most Likely You Go Your Way (and I’ll Go Mine),” one of several raucous put-down songs from Blonde on Blonde. Before 1989, Dylan hadn’t played the song live since the Rolling Thunder Revue in 1976. “You Go Your Way” became the standard opener throughout the summer of 1989.

Like legendary leadoff hitter Pete Rose, the song works effectively at the top of the order to set the table for the evening’s performance. I’ll quote the lyrics Dylan actually sings, which differ somewhat from the published lyrics and album version:

You say you love me

You’re thinkin’ of me

But you know you could be wrong

You say you told me

That you wanna hold me

But you know you’re not that strong

Sometimes it gets so hard to care

It can’t be this way everywhere

Gonna let you pass

I’ll go last

Time will tell who has fell

Who’s been left behind

When you go your way and I go mine

Ostensibly this is a relationship song, where the singer lets his lover know he’s grown tired of her and is ready to move on. However, in the context of live performance, the song doubles as a direct address to the audience. The singer essentially poses an ultimatum to his fans—love me or leave me—I’ll be fine either way. Audiences carry a lot of baggage to Dylan concerts: identification with the icon’s various personae, songs they’re hoping to hear, familiar arrangements imprinted in their memories, etc. The singer has repeatedly and unabashedly defied those expectations, insisting upon going his own way. This opening song sets the navigational terms for the concert to follow: either they will go along for the ride by following Dylan down his new performance path, or they’ll part ways with him at his latest musical crossroads.

Sticking with Blonde on Blonde, next up is “Absolutely Sweet Marie.” Remarkably, Dylan had never played this fantastic song live until the previous summer. He only performed it in 4 of his 51 concerts in the summer of 1989, so this one is an absolutely sweet treat.

The song is played as a driving rocker at Riverbend ’89. The performance, both musically and vocally, is turbo-charged, until a very strange slow-motion conclusion. It’s as if, after throwing all fastballs, the band hurls an unexpected off-speed pitch at the end. Judging by the bootleg of “Absolutely Sweet Marie,” Dylan and mates have their good stuff going tonight and are in complete command of all of their pitches.

The third song is an electric version of “Ballad of Hollis Brown.” It was a mainstay of the 1974 tour but didn’t return as a setlist regular until the summer of 1989. [Dylan played the song at Live Aid in 1985, but the less said about that debacle the better.] This terrifying song from The Times They Are A-Changin’ tells the story of a poor South Dakota farmer driven by deprivation and despair to kill his wife, five children, and finally himself.

The resurrection of “Hollis Brown” was surely a response to the searing cover by The Neville Brothers.

Dylan first heard their version during the making of Yellow Moon, produced by Daniel Lanois and released in the spring of 1989. He was so impressed with the production, particularly on the Nevilles’ two Dylan covers (“Hollis Brown” and “With God on Our Side”) that he invited Lanois to produce his next album Oh Mercy. Dylan and the band gradually amp up the intensity at Riverbend ’89, mirroring Hollis Brown’s relentless thoughts as they escalate toward violence.

The standout of the first electric set is “Watching the River Flow.” Dylan only played the song three times in 1989, and the last was this exuberant performance in Cincinnati. He sings the words so quickly that, if you’re not already familiar with the lyrics, you’re unlikely to understand half of what he’s slurring and slinging. But this one isn’t an exercise in elocution; it’s the sonic equivalent of whitewater rafting. The band is paddling for their lives, and Dylan obviously relishes guiding his crew through the rapids.

Over the course of Dylan in Cincinnati, I frequently stress the principle that where and when a song is performed has an important impact on how it’s played and how it’s received. “Watching the River Flow” is a perfect marriage of song and venue. The Ohio River flows right behind the Riverbend Music Center. Backstage before or after the show, Dylan could literally sit on the riverbank and watch the mighty Ohio flow. Onstage, he can watch the flotsam and jetsam of humanity flowing in front of him, set into motion by his river song. And from the audience’s perspective, the music issuing from the stage is the fast-flowing river they’re sitting and watching—or standing and dancing along with glee.

In his book How Music Works, Talking Heads lead singer David Byrne considers the importance of context in shaping songs. He writes in the preface that “the same music placed in a different context can not only change the way a listener perceives that music, but it can also cause the music itself to take on an entirely new meaning.” Invoking his title, Byrne asserts, “How music works, or doesn’t work, is determined not just by what it is in isolation (if such a condition can ever be said to exist) but in large part by what surrounds it, where you hear it and when you hear it” (9).

Case in point: “Watching the River Flow” at Riverbend ’89. I’ve always liked the song as recorded in 1971, and Dylan has reconnected with it in recent years, making it a mainstay of his post-pandemic setlist. But I’ve never heard a more satisfying rendition than this rollicking live performance, which is perfectly situated, in the words of the old murder ballad, “Down beside where the waters flow / Down by the banks of the Ohio.”

All of the songs in the first electric set end with a slow-roll outro. This is clearly a deliberate strategy the band is experimenting with. I’m no musician, so I can only speculate about what’s going on here. I wonder if it has something to do with the ever-evolving NET setlists. Dylan is notoriously difficult to play with because he is musically improvisational but verbally uncommunicative on stage. One of the consequences of his spontaneity is that his bandmates are, by design, never completely sure what he’s doing or where he’s going. For the purposes of Dylan in Cincinnati I’ll use a Bengals football analogy.

These slow transitions between songs seem to function like quarterback Joe Burrow calling signals at the line of scrimmage during the no-huddle offense. The band is moving too quickly to ever grind completely to a halt. But the outro pause between songs at least gives them a chance to relay what play they’re preparing to run before the ball is snapped. It’s wild to think that, at times, the band may be almost as surprised as the audience about what audible Dylan will call next.

The pattern is most conspicuous in “I Want You.” It’s almost like two songs in one at Riverbend ’89. First there’s the brisk delivery, quicker than the familiar recorded version on Blonde on Blonde, but still recognizable. Then, after Dylan is done singing the lyrics, he uses his harmonica to maneuver the music like a jockey guiding his mount at neighboring River Downs (now called Belterra Park).

“Art is a disagreement,” Dylan asserts in The Philosophy of Modern Song (35). You can hear the musicians having a disagreement in the second half of “I Want You.” When Dylan starts playing harmonica, he’s ready to slow the pace. But drummer Chris Parker continues to keep time like he’s running in the Kentucky Derby. Dylan tries to rein him in, but Parker isn’t getting the message, so G. E. Smith intervenes on guitar. At first it sounds like Smith’s guitar is responding to Dylan’s harmonica: “Is this what you want, Bob? Or maybe this?” But after repeated listening I’ve convinced myself that Smith is mainly trying to get Parker’s attention. The drummer stops playing entirely once he realizes that the boss wants a harmonica solo at his own gait, a walk not a gallop. It’s a rambunctious ride, but they finally cross the finish line. Rough and rowdy, yes, but also very revealing with respect to the dynamics of live performance and the evolution of Dylan’s NET sound.

The 1989 sound is noticeably different than 1988. The preoccupation this summer is with timing and speed control: fastfastfast followed by slowslowslow. Do you ever work out at the gym and find yourself near one of these sprinters running at breakneck speed on the treadmill—but then they’ll periodically lift themselves off the belt and straddle it motionless for a short time, before resuming their bat-out-of-hell shenanigans? I think it has something to do with working out the heart like a muscle through radical variations of heartrate. That’s kind of what Dylan’s arrangements tonight sound like: a musical workout. He’s putting the band through its paces, experimenting with rapid transitions between different speeds. Much like the treadmill analogy, it feels like some kind of endurance test. Dylan apparently doesn’t like to let the band get too comfortable, preferring instead to keep them guessing. Furthermore, since the band had a rookie on this tour—bassist Tony Garnier—it may have been an orientation strategy (boot camp? hazing ritual?) for showing the newcomer how this band takes care of business.

Dylan seems most interested in creating soundscapes in this concert, emphasizing the music surrounding the words. So much of his august reputation rests upon his power with words: as voice of his generation and poet laureate of rock. But here he curates a mood through music at least as much as through lyrics. This approach continues in the middle acoustic set. You can hear the same fastfastfast delivery followed by a slowslowslow outro on “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright.”

Dylan’s vocals are spirited, and there’s some wonderful acoustic jamming with Smith. Then he slows things down with a beautiful harmonica solo. Much like Parker in “I Want You,” Smith eventually backs off and gives Dylan room to play his harp, unaccompanied and unhurried. Musically, that’s the whole Riverbend ’89 concert: wheels on fire bounding down the road until they incinerate in a blaze of glory.

Dylan really seems to have fallen back in love with the harmonica this summer, playing it on 8 of the 16 songs at Riverbend ’89, including 6 in a row at one point. By comparison, he didn’t play the instrument a single time at Riverbend ’88. Not every listener loves Dylan’s harmonica. Students in my first-year seminar on Dylan routinely regard it as an instrument of torture, groaning every time he plays the bloody thing. But if you love Dylan’s harmonica then this is the concert for you.

There’s another long and searching solo at the end of “One Too Many Mornings.”

Half the total length of the song comes after Dylan is done singing. He is feeling his way musically onto new sonic terrain, and he takes his time doing it. His harmonica and acoustic guitar serve as headlamp and pickaxe as he tunnels deep into the mineshaft of this song.

The one acoustic holdover from Riverbend ’88 is “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll,” but again the performance a year later is notably different. To be honest, Dylan drifts in and out of focus during his vocals: the first verse about Zanzinger is rushed and flat; the Hattie Carroll verse wakes him up and he’s locked into portraying her plight with poignant commitment; but then he’s goes lax for an anticlimactic account of the courtroom scene and verdict.

Had I stopped listening after Dylan was done singing, then I would have rated it as a pedestrian interpretation of a great song. What salvages the performance and turns it into something special is the 2 ½ minutes of acoustic guitar and harmonica playing after the final verse. The Riverbend ’88 “Hattie Carroll” was 5 ½ minutes long—Riverbend ’89 stretches out to 8 minutes. As lyrical storyteller, Dylan never spells out his feelings about the systemic racism and injustice displayed in this song: he lets the baleful situation speak for itself. But in this performance, he communicates first outrage and then sorrow—wordlessly but irrefutably—through guitar and harmonica, his most eloquent tools of expression this evening.

Second Electric Set & Encore

When you read the full setlist from Riverbend ’89, one odd selection really stands out in the second electric set. Wedged in between “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35” and “Silvio,” Dylan turned back the calendar and flipped through the American songbook to pluck out the old standard “I’m in the Mood for Love.”

Talk about defying audience expectations! What must the Cincinnati crowd in their tie-dye t-shirts and peace-symbol tattoos have thought when their folk-rock hero began crooning this torch song, written by Dorothy Fields and Jimmy McHugh in 1935, and popularized by the likes of Frances Langford, Billy Eckstine, and Nat King Cole before many of them were born and Bobby Zimmerman was still in knee pants? Dylan had been in the mood for this song all week: this was the third night in a row he sang it. He only played “I’m in the Mood for Love” live four times ever—and this was the very last performance.

And you know what? It sounds pretty damn good! Post critic Larry Nager was both surprised and impressed:

After a 27-year career that has run from folk to rock, gospel and the Traveling Wilburys, one never knows what to expect from Bob Dylan in concert. Even so, none of the 5,746 at Riverbend Thursday night could have predicted he’d croon ‘I’m in the Mood for Love.’ But he did, and, accompanied by guitar master G. E. Smith, former Asleep at the Wheel bassist Tony Garnier and drummer Christopher Parker, Dylan did a fairly good job of it. (6C)

Enquirer critic Cliff Radel snarkily added, “he could not have a second career as a crooner” (B-2). More than a quarter-century later, Dylan would prove Radel wrong. In the second decade of the 21st century, he released three albums of standards [Shadows in the Night (2015), Fallen Angels (2016), and Triplicate (2017)] and reoriented his NET setlists toward the new (i.e., old) material.

Performances like “I’m in the Mood for Love” at Riverbend ’89 show that this idea may have been germinating for a long time. You might expect the iconoclastic rebel to snub songs like this as the antithesis of his music and ethos. Nope. He sings this sentimental song with sensitivity and love. This is not Sid Vicious covering “My Way.” This is Willie Nelson’s Stardust.

Dylan closes the second electric set with “Like a Rolling Stone.” He challenges himself to see how fast he can deliver the lines in each verse. Listening to the bootleg, you especially notice the speed differential when the crowd sings along with the chorus. They’re singing the song as memorized from Highway 61 Revisited; meanwhile, Dylan races by them in the passing lane. At times he races past his own band, too, with the fans’ seemingly more in sync with the rhythm section than the frontman.

Things get really weird near the end of “Like a Rolling Stone.” The music starts to slow down, and you think “Here we go again with another slo-mo outro.” But then it speeds up into a totally different tune and you think “Okay, they’re transitioning into another song, but what is it?” The answer is . . . nothing. It’s a tease or a miscommunication, and instead the band grinds down to a halt. According to drummer Chris Parker, this sort of confusion was common when Dylan performed his big hits: “We didn’t play the same thing twice. Play something different every night, or play something that is current to that night. That happened a lot, especially on familiar tunes, like ‘Rainy Day Women’ or ‘Times They Are a-Changin’.’” Tonight we can add “Like a Rolling Stone” to the list, which sounds “Like a Big Hot Mess” at Riverbend ’89. The audience sounds disoriented for a moment, delaying their cheers for an encore until they’ve figured out if the song and set are finished or not.

It can be hard to fathom why a bandleader would want to confuse his own band and audience in this manner. The effect sounds discordant and the motives might seem perverse. This is a familiar pattern for Dylan during the NET years, and it’s a bargain one accepts in playing with him live on stage, watching him from the audience, or listening to him on bootlegs. Laura Tenschert describes this unruly performance tendency from a fan’s vantage point:

Sometimes it feels like he’s just noodling around or pressing down on the keys, rather than trying to play with the band. Sometimes this sounds really jarring, or sometimes it’s even almost a bit funny. But I’ve also seen it with my own eyes that sometimes Dylan does something, that by all accounts shouldn’t work, and plays a figure on the guitar that goes completely against what the band is playing, but he forces the notes to make sense in the context. It’s also obviously because he has a great band who molds their playing around what he is doing in the most extraordinary way. Which leads me to believe that he does these things to challenge the band and really get them out of their comfort zone. This also comes from playing the same songs every night. He does not want them to get comfortable.

Dylan explained his exploratory process on stage in a 1989 interview with Edna Gundersen: “There’s always new things to discover when you’re playing live. No two shows are the same. It might be the same song, but you fin different things to do within that song which you didn’t think about the night before. It depends on how your brain is hooked up to your hand and how your mind is hooked up to your mouth” (qtd. Muir 38). Sometimes it feels like Dylan’s brain, hands, and mouth are hooked up to a different song than the one the band is playing, as with the Riverbend ’89 performance of “Like a Rolling Stone.”

Ah, but when it does work—when Dylan and the band break free from the inertia of habit and startle themselves and the audience with a fresh discovery right there on stage—then the results are magical and one-of-a-kind. Those epiphanies cannot be predicted or scheduled, and they certainly don’t happen every night. But Dylan is willing to try and fail and try again, risking frustration or embarrassment or confusion—Captain Aha! in search of the elusive white whale of spontaneity—on the off chance that the musicians might pierce through the veil of mystery, tumble into ecstasy, and spontaneously create something new, alive, and transcendent.

As a bootleg listener, I experience just such a transcendent moment during the encore performance of “Mr. Tambourine Man.” There’s a good chance that Dylan played this song at one or both of his 1965 concerts in the city, but since no setlists or bootlegs survive from those first two shows, this is the first recording I have of this masterpiece in Cincinnati. So that already makes it very special. Dylan’s singing is clear, though a bit rushed in the first half of the song. But it’s the sensitive guitar work in the second half, and especially Dylan’s majestic harmonica in the outro, that leaves me spellbound.

On one important level, the song is about wandering in pursuit of the muse of creative inspiration—and that is precisely what we hear Dylan doing through his probing harp playing after the final verse. I’m not sure if he finds what he’s looking for, but the groping search characterizes his approach throughout this concert. Again, he is in absolutely no hurry to end this song. You wonder if he’ll ever stop playing that harmonica, and I for one would have been content to follow wherever he goes for as long as he wants. It’s enthralling for most of the crowd, except for a few yahoos who keep breaking the trance with self-indulgent hoots and yelps. Stop interrupting my worship, you blasphemous bastards! Don’t you realize that you’re in the presence of genius?

The malcontents had the last word in the local press, too. Larry Nager was deaf to Dylan’s musical explorations, dismissively noting how “he tore through song after song, occasionally tootling tunelessly on his harmonica” (6C). How can that be all that you heard? Nager goes on to claim: “For the most part, Dylan seemed content to go through the motions one more time” (6C). False! You’re way wrong there, Mr. Nager.

You might not like what he’s doing—I’m not always entirely sold on every creative swerve either—but it’s flatly inaccurate to say that Dylan is coasting through a routine performance. He’s spinning the wheel, rolling the dice. Like Pete Rose, Dylan didn’t win all his bets, but he sure as hell made plenty of them on this hot August night in Cincinnati.

Nager especially raises my hackles with this scathing swipe: “Smith and Dylan ended almost every song with instrumental flourishes that dragged on, becoming metaphors for Dylan’s career—long after he had nothing left to say, he still didn’t know when to quit” (6C). Nothing left to say? Quit?? Ha! I shouldn’t even bother to get upset about such an absurd comment. Needless to say, Nager lost that bet. As it turns out, Dylan still had so much left to say that he wasn’t even halfway through his career in 1989. Dylan’s more accurate self-assessment of this period is worth repeating: “I saw that instead of being stranded somewhere at the end of the story, I was actually in the prelude to the beginning of another one” (Chronicles 153).

Thankfully, the Bob Dylan story turned out much better than the Pete Rose story. Unlike Rose, a beloved icon from the sixties and seventies who experienced an epic fall from grace in the following decade, Dylan enjoyed a resurgence of creativity in the late eighties. The key to Dylan’s rejuvenation was his head-first slide into live performance on the Never Ending Tour.

Once upon a time, 1988 to be exact, Dylan came to Riverbend Music Center with a new band and a new plan. He reinvented himself yet again by reimagining his songs and reconfiguring his approach to live performance. That worked so well that he reinvented the reinvention the following year, proving Heraclitus right (if he had lived 2,600 years later in Cincinnati) that Dylan never steps in the same Riverbend twice. At his first two NET concerts in the city, Dylan set a high bar for creative innovation, a standard of excellence he would continue to meet more often than not in decades to come.

For the next installment, we’ll be skipping ahead ten years to the best Dylan concert I ever attended in Cincinnati. Prepare yourself to enter the time machine once again as we set our sights on the legendary Bogart’s show in 1999.

Works Cited

Baez, Joan, with The Greenbriar Boys. “Banks of the Ohio.” Joan Baez, Vol. 2. Vanguard, 1961.

Byrne, David. How Music Works. McSweeney’s, 2012.

Dylan, Bob. Chronicles, Volume One. Simon & Schuster, 2004.

---. Official Song Lyrics. The Official Bob Dylan Website,

http://www.bobdylan.com/.

---. The Philosophy of Modern Song. Simon & Schuster, 2022.

Gundersen, Edna. Interview with Bob Dylan. USA Today (September 1989), in Andrew Muir, The True Performing of It: Bob Dylan & William Shakespeare, updated edition (Red Planet Books, 2020).

LB-01200. Bootleg Recording. Taper unknown. Remastered by Paul Loeber. Riverbend Music Center, Cincinnati (10 August 1989).

Nager, Larry. “Dylan show up, down like career.” Cincinnati Post (11 August 1989), 6C.

Padgett, Ray. “Drummer Christopher Parker on the Start of Bob Dylan’s Never Ending Tour,” Flagging Down the Double E’s (26 September 2021),

---. Interview with Ray Benson. Pledging My Time: Conversations with Bob Dylan Band Members. EWP Press, 2023.

Radel, Cliff. “Bob Dylan went his way—more’s the pity.” Cincinnati Enquirer (11 August 1989), B-2.

Tenschert, Laura. “Episode 25: The ‘Never Ending Tour,’ Part 1.” Definitely Dylan (15 July 2018), https://www.definitelydylan.com/listen/2018/7/15/episode-25-the-never-ending-tour-part-i.

Great stuff GH. Wow, imagine getting both River Flow AND Most Likely in the same show - imagine that lol. The more things change...

I am so in love with the sports metaphors here. But most of all, Graley, I love how just like Bob you are using the freedom of a different medium from academic writing to experiment with different approaches. I just reread your phenomenal but very serious chapter on race and Dylan and now this really playful entry on Shadow Chasing. I leave each one of these wishing I could write like you.