[Note: What follows is a slightly longer version of my talk “Mr. Tambo & Mr. Bones, Play a Song for Me: Foster & Poe in Dylan’s “Nelly Was a Lady” Chapter,” presented as part of the panel “The Art and Philosophy of The Philosophy of Modern Song” at the World of Bob Dylan 2023 Conference in Tulsa. Many thanks to conference director Sean Latham and his team, as well as my extraordinary co-panelists Elizabeth Cantalamessa and Laura Tenschert.]

Robert Hunter, longtime Grateful Dead lyricist and sometime Dylan collaborator, wrote an interesting foreword to David Dodd’s book The Complete Annotated Grateful Dead Lyrics. In his opening paragraph he observes, “When fans hear a song they like, they internalize it, dance to it, sing along. Tape it, collect it, trade it. When scholars hear a song they like, they annotate it” (Dodd xi). Now, if this were a Dylan talking, I’d expect him to throw in a dig at nerds like us who waste our time annotating his songs. But instead Hunter offers a more sympathetic view: “There is more than one way to love a song. There are as many ways as there are listeners” (xi).

Amen! Hunter appreciates that annotation—the shadow chasing of tracking down allusions to their original sources—isn’t an attempt to minimize, sterilize, or euthanize a song: it’s just another way to love it. The same holds true for The Philosophy of Modern Song. Writing the book is just another way for Dylan to love the songs of other artists. But sometimes his love speaks like silence: the art of the unsaid.

He devotes a chapter to “Truckin’,” a song written by Robert Hunter and performed by the Grateful Dead (and by Dylan in his 2023 Japanese tour). He describes Hunter as “steeped in the songs of Stephen Foster” (138). David Dodd identifies several Foster allusions in Hunter’s lyrics, including “the Doo-dah man” in “Truckin’,” a reference to Foster’s “Camptown Races” [“Camptown ladies sing this song / Doo-dah! Doo-dah!”].

Dylan is also steeped in the songs of Stephen Foster. He acknowledged his debts to Foster long ago. Readers of Shadow Chasing are probably familiar with his touching rendition of “Hard Times” on Good as I Been to You (1992). In a 1985 interview with Robert Hilburn, Dylan reflected on his role models for songwriting: “But you can’t just copy somebody. If you like someone’s work, the important thing is to be exposed to everything that person has been exposed to. Anyone who wants to be a songwriter should listen to as much folk music as they can, study the form and structure of stuff that has been around for 100 years. I go back to Stephen Foster” (1337).

In that same interview, Dylan tipped his cap to another artistic mentor from the 19th century: “I had read a lot of poetry by the time I wrote a lot of those early songs. I was into hard-core poets. […] Poe’s stuff knocked me out in more ways than I could name” (1340).

Maybe he couldn’t name it then, but he has been naming Poe lately. He name-drops the poet in “I Contain Multitudes”: “Got a tell-tale heart like Mr. Poe / Got skeletons in the walls of people you know.” Dylan may also be nodding in Poe’s direction by naming his book The Philosophy of Modern Song, which sounds an awful lot like Poe’s essay “The Philosophy of Composition,” a detailed explanation of how he wrote his most famous poem “The Raven.”

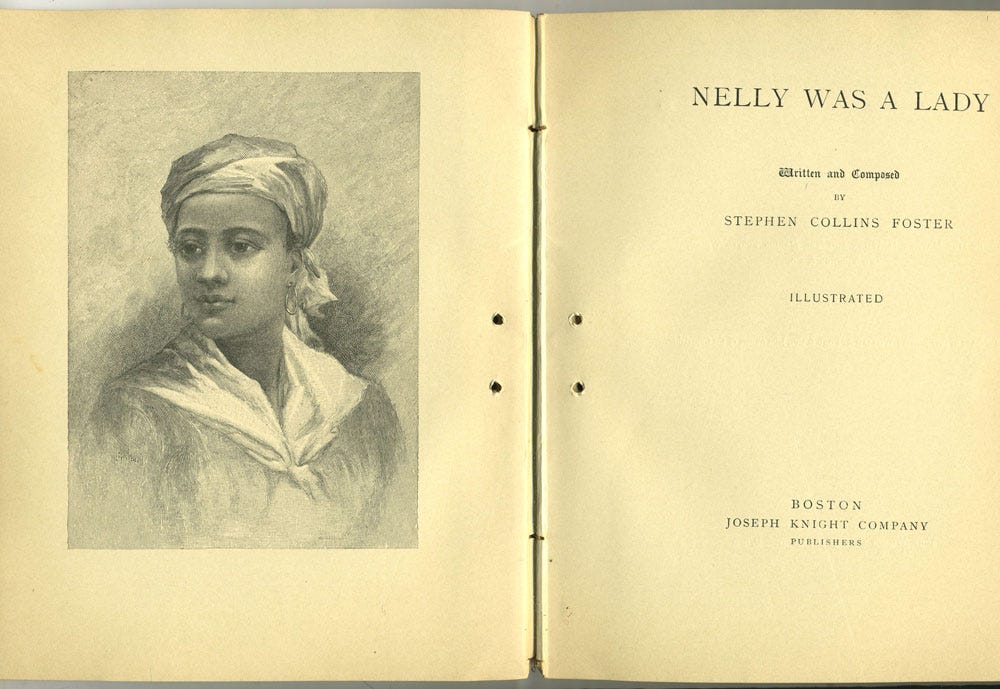

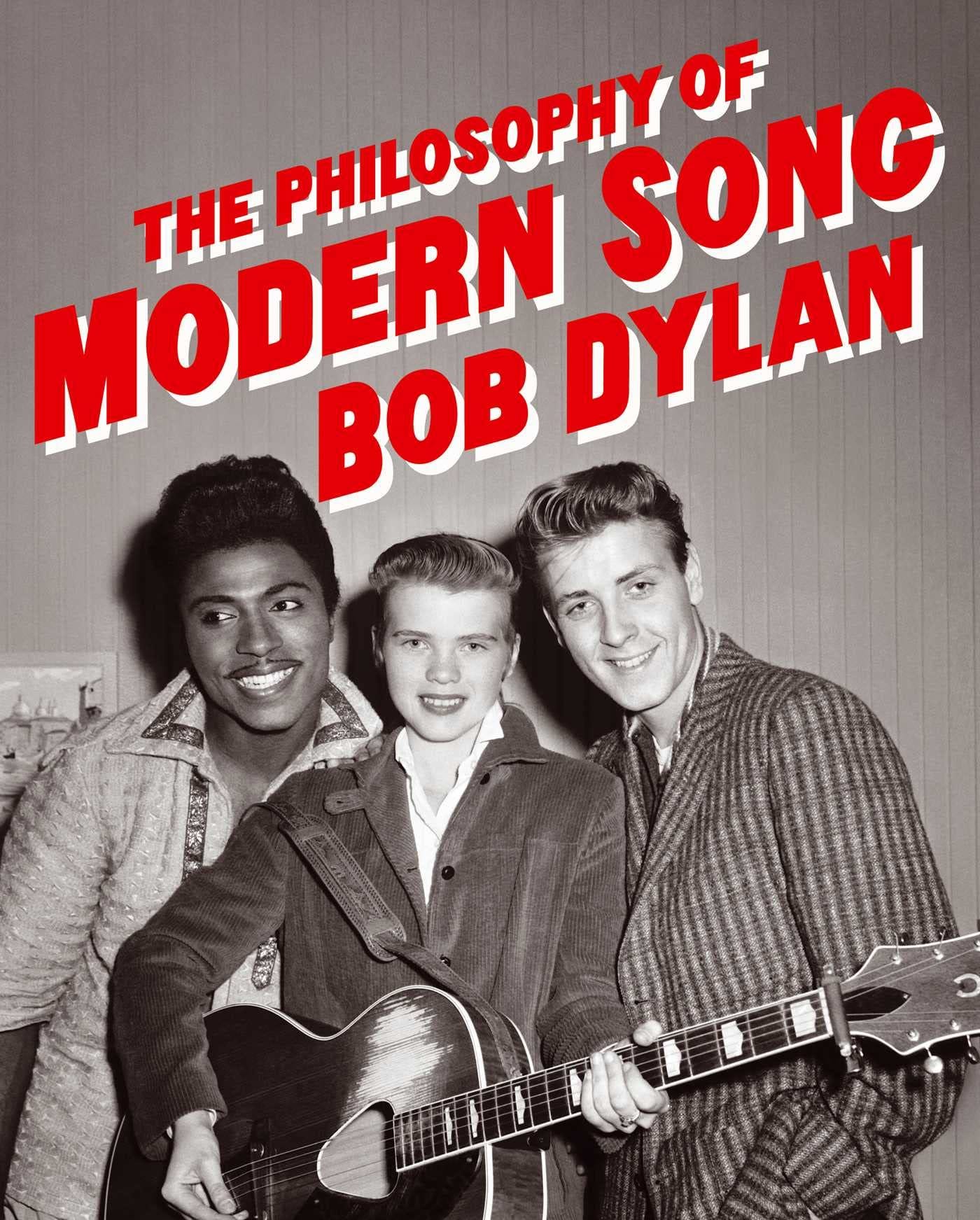

In Chapter 24 of The Philosophy of Modern Song, Dylan focuses “Nelly Was a Lady,” composed by Stephen Foster in 1849. Like many chapters, this one is very brief, consisting of a 5-paragraph riff followed by a 2-paragraph commentary, accompanied by one full-page and two half-page pictures.

There’s a lot more going on here than first meets the eye—lots of breadcrumbs left for us annotators to trace back to their sources. Dylan’s most explicit statement of what he’s up to comes in the first sentence of the commentary: “Stephen Foster is the counterpart to Edgar Allan Poe” (115). He just drops that stone in the water and lets it sink. But a sinking stone gathers ripples. I want to follow some of those ripples through a series of annotations connecting Poe and Foster to one another and to their counterpart Dylan.

Poe published “The Raven” to instant acclaim in 1845, and he wrote “The Philosophy of Composition” the following year. In the essay he asserts: “the death […] of a beautiful woman is unquestionably the most poetical topic in the world, and equally is it beyond doubt that the lips best suited for such topic are those of a bereaved lover.” Pretty creepy if you think about it— a beautiful woman must die in order for a man to mourn her loss beautifully. The canons of poetry and song are filled with countless examples, including “Nelly Was a Lady.” The opening verses depict this very same scenario:

Down on the Mississippi floating,

Long time I travel on the way.

All night the cottonwood a-toting,

Sing for my true love all the day.Now I’m unhappy, and I’m weeping,

Can’t tote the cottonwood no more;

Last night, while Nelly was a-sleeping,

Death came a-knocking at the door.Nelly was a lady.

Last night, she died.

Toll the bell for lovely Nell,

My dark Virginia bride.

Here is Dylan’s translation of the singer’s situation:

You’re hauling the timber on the grand river, the big river, river of tears, manifest destiny—you hoist the cottonwood logs, the silver bark poplars, that make bright shiny tables and furniture, but you’ve reached the station in life where the work is meaningless, and it’s been this way ever since grief came to knock. Knocking when the cock crowed—grief and gloom in the first light of morning, knocking out the bright lights of the heavens. (113)

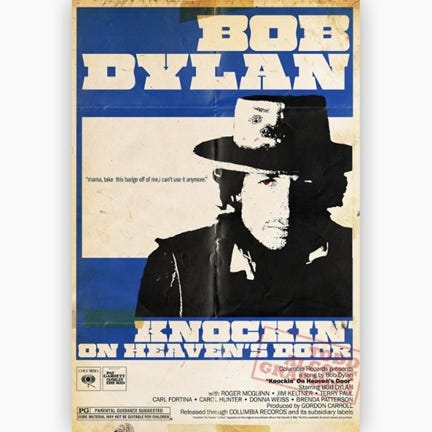

There’s a lot worth annotating here. Let’s begin with that knock-knock-knocking. We cannot miss the self-allusion to Dylan’s own song “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door.” He does this repeatedly in The Philosophy of Modern Song, forging understated links between the songs he comments on and the songs he composed.

I also hear strong echoes of Poe. Death comes a-knocking at the door in “The Raven,” too. The grief-stricken narrator first mistakes a person (or a ghost) rapping at his chamber door before realizing it is a bird at his window. Readers will doubtlessly hear another Dylan echo from the end of “Love Minus Zero / No Limit”: “My love she’s like some raven / At my window with a broken wing.”

Poe’s speaker grows increasingly frantic, interrogating the bird about its motives. He desperately seeks a message from his dead lover Lenore, some sign that they will one day be reunited. Unfortunately, he gets nothing from the raven but croaks, which he hears as “Nevermore.” Lenore, Eleanor, Nell, Nelly—it’s basically the same name. Both Poe’s “The Raven” and Foster’s “Nelly Was a Lady” dramatize the same circumstances: a first-person widower mourning beautifully for his dead wife. Dylan hears those intertextual echoes and writes a riff that at times could apply just as well to either work, as well as to some of his own songs. Poe, Foster, Dylan. I even wonder if he had elegiac trio in mind when he inserted an image of three time-scarred mausoleums in Chapter 24.

“My dark Virginia bride.” Let’s pause over Virginia. After Poe’s father abandoned the family, his mother moved them to Richmond, Virginia. He briefly attended the University of Virginia but had to drop out because he couldn’t afford tuition. If you know anything about Poe, it’s probably that he wrote scary stories, was a drunk and drug fiend, and married his 13-year-old first cousin. You may also recall the name of his child-bride: Virginia Clemm.

She died at the tender age of 24, and 40-year-old Poe followed her into the grave two years later in 1849, the same year Foster wrote “Nelly Was a Lady.”

“My dark Virginia bride.” Why dark? Because the singer and his lost love were slaves. What Dylan conspicuously neglects to mention in Chapter 24 is that “Nelly Was a Lady” was written by Foster for the minstrel stage and was originally performed in blackface and in dialect.

Remember what Dylan told Hilburn when discussing his influence from Foster: “If you like someone’s work, the important thing is to be exposed to everything that person has been exposed to” (1337). Dylan doesn’t explicitly reference Foster’s background and the minstrel roots of “Nelly Was a Lady,” but he did his homework and sneaks in obscure footnotes.

For instance, here’s an example of Dylan’s clever sleight of hand. This is from the Jeff Slate interview Dylan gave about The Philosophy of Modern Song. Slate asked him if it matters where you first hear a song. Dylan’s meandering answer makes you wonder if he’s lost marbles, or at least his train of thought:

One of my granddaughters, some years back, who was about 8 at the time, asked me if I’d ever met the Andrews Sisters, and if I’d ever heard the song ‘Rum and Coca Cola.’ Where she heard it, I have no idea. When I said I’d never met them, she wanted to know why. I said because I just didn’t, they weren’t here. She asked, ‘Where did they go?’ I didn’t know what to say, so I said Cincinnati. She asked me if I would take her there to meet them. Another time, one of the others asked me if I wrote the song ‘Oh! Susanna.’ I don’t know how she heard the song, or when, or what her relationship to it is, but she knows it and can sing it. She probably heard it on Spotify. (Slate)

Dylan is crazy like a fox. I suspect he knows that the Andrews Sisters are not from Cincinnati but rather from his old stomping grounds in Minneapolis—even an 8-year-old could Google it. I guarantee you the “Oh! Susanna” reference isn’t arbitrary. Stephen Foster worked as a bookkeeper for his brother’s shipping company in Cincinnati from 1846 to 1850. The offices of Irwin & Foster overlooked the bustling Ohio River wharf where goods were loaded and unloaded onto steamboats. Foster also frequented the bars and theaters of Cincinnati, where traveling minstrel shows did booming business. Inspired by what he saw on the wharf by day and the stage by night, he wrote several of his most famous songs while living and working in Cincinnati, including “Oh! Susanna” and “Nelly Was a Lady.”

Intrigued by Foster’s local connections to my adopted hometown, I went downtown to walk in his footsteps. He lived at a boarding house on Fourth Street.

For many years afterwards, the building was converted to the Guilford School, and today it contains corporate office space and a fitness center. I found a commemorative plaque on the front of the building that reads: “On the site of this school between the years 1846-1850 lived Stephen C. Foster, master of the art of song, composer of ‘My Old Kentucky Home,’ ‘Swanee River,’ ‘Old Black Joe,’ and many others. In native ballad form and melodic strain distinctively American, he sang of simple joys and pathos to all the world.”

We know that Dylan sometimes likes to visit homes where songwriters he admires lived in their youth. I don’t know if he ever visited the Guilford School building, but it would have been easy to do. Walk a couple blocks northwest from Foster’s former residence and you’ll run into Taft Theatre, where Dylan played his first concert in Cincinnati in March 1965, and where he returned to play in 2007. I made that short stroll myself, and on the way I was delighted to pass by the Edgar Apartments building. Total coincidence, of course, but a delicious one. Even the streetscape of Cincinnati invites connections between Foster, Poe, and Dylan.

Foster is sometimes called “the Father of American Music,” but much of his legacy now seems offensive and destructive. He perpetuated derogatory racist stereotypes through his so-called “Ethiopian melodies.” Foster frequently indulged the myth of slaves pining with nostalgic affection for Southern plantation life. Hell, he more than indulged it: he was one of the myth’s chief architects, and he cashed in on the popularity of this fraud through his popular minstrel songs. But, if you study blackface minstrelsy in any depth, as Dylan clearly has, then you’ll also learn that it’s more complicated than that.

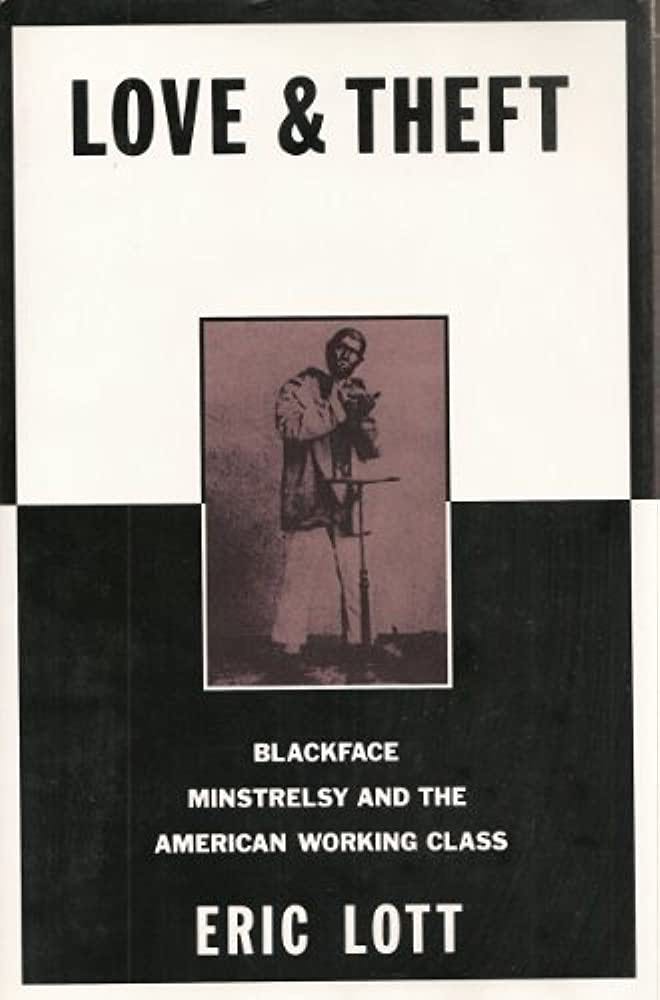

Readers of this newsletter may be familiar with the 1993 book published by Eric Lott titled Love & Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class.

Dylan was apparently familiar with at least the title, since he borrowed the idea for his 2001 album “Love and Theft,” a collection of songs steeped in the minstrel tradition.

While fully acknowledging the fundamental racism of blackface minstrelsy, Lott also finds other economic, ideological, and psychological forces at play in the tradition, including envy, class-conscious anxiety, and desire—in short “love and theft.”

Foster penned many famous minstrel songs, but Dylan’s choice to focus on “Nelly Was a Lady” is telling. Scholars often credit this song as a turning-point in Foster’s career, where he pivoted away from racial mockery in favor of sentimental ballads designed to elicit sympathy. The singer demands dignity for Nelly. She is not a figure for ridicule. She is a lady, and she deserves respect and commemoration. Dylan makes a redemptive gesture of his own by spotlighting Alvin Youngblood Hart’s version of the song. Hart is an African American blues singer, and his sensitive interpretation isn’t tarnished by blackface appropriation. “Alvin sings the song in its pure form,” as Dylan puts it (115).

But. There’s only so far one can go to purify “Nelly Was a Lady.” We shouldn’t pussyfoot around by whitewashing out the burnt cork. You might accuse Dylan of laundering or redacting Foster’s reputation, giving him a free pass and an undeserved promotion, by setting him up as counterpart to Poe, instead of minstrel patriarchs like Daddy Rice or Dan Emmett. If Dylan wants to put Foster’s work in conversation with Poe’s, fine, but it seems worth mentioning a fundamental distinction, namely that “Nelly Was a Lady” is “The Raven” in blackface.

As composed by Foster and sung by Alvin Youngblood Hart, it’s a genuinely moving ballad. “A lot of sad songs have been written,” writes Dylan, “but none sadder than this” (115). However, viewed in its original context— published in Foster’s Ethiopian Melodies and performed by the Christy Minstrels—the song was tangled up in blackface. No matter how sympathetic Foster’s intentions may have been, he was working within a denigrating theatrical form dedicated to the proposition that all men were not created equal.

Now let me dismount my high horse and give Dylan some credit. In certain subtle but unmistakable ways, he signals his awareness of the problematic minstrel history behind “Nelly Was a Lady.” Let’s return to a line I quoted earlier and reconsider it from another angle. “You’re hauling timber on the grand river, the big river, river of tears, manifest destiny” (113). What’s that last phrase doing in there?

As a student of 19th-century American history, Dylan knows that the concept of “Manifest Destiny” had specific significance for that era. American nationalists believed it was the divinely ordained mission of the United States to expand its dominion over the continent, spreading democracy and capitalism, and seizing land from indigenous people and people of color. Manifest Destiny was the driving force behind the Mexican-American War (1846-1848) which greatly expanded U.S. territory out west. Stephen Foster stayed back in Cincinnati and helped run the office while his brother Dunning went south to fight in the Mexican-American War.

Another sign that Dylan is conscious of context comes in the final paragraph: “The guitar turnarounds are a slow cakewalk between heartbroken verses, loss shared on the front porch” (115). The cakewalk originated as a Black dance tradition in the U.S. South around the mid-19th century. Blackface minstrels soon recognized that the cakewalk made for a highly entertaining spectacle in live performance, however, and started working these numbers into their shows. By the late 19th-century, cakewalks were routine on the minstrel stage.

Dylan’s cakewalk reference isn’t accidental here. But it’s not elaborated upon either. He gestures obliquely in the direction of minstrelsy, but he doesn’t spell it out, leaving us annotators to lift that barge and tote that bale.

In my book on Time Out of Mind, I interpret the songs recorded for that album as a series of dreams working on multiple levels. In the final chapter, I argue that, on one of level, the singer dreams his way into the experiences of a fugitive slave. This imaginative exercise may be what prompted Dylan to start considering his own work in relation to the minstrelsy tradition with greater scrutiny and urgency.

Something certainly sent him down this path, because it kept reappearing in various guises in the first decade of the 21st century. I’ve already mentioned the minstrel show influence on 2001’s “Love and Theft.” In 2003, Dylan co-wrote and starred in the film Masked and Anonymous, which includes his performance of the minstrel staple “Dixie” and an encounter with the ghost of a minstrel performer (Ed Harris in blackface).

In 2006, he extended the pattern on the album Modern Times, lifting several lines from the so-called “Poet of the Confederacy” Henry Timrod, and reworking an old minstrel song into the haunting ballad “Nettie Moore.” [My friend Rob Reginio has an excellent chapter on this song in Highway 61 Revisited: Bob Dylan’s Road from Minnesota to the World.] Then his fascination for the subject seemed to fade. Or maybe it just got channeled into the descendants of the minstrel legacy: the songs of Tin Pan Alley, Dylan’s major musical interest in the second decade of the 21st century.

Now in the century’s third decade, he reminds us that minstrelsy is a recessive gene in the DNA of modern song. Dylan focuses his final chapter on “Where or When.” The song was written by Rodgers & Hart for their 1937 musical Babes in Arms, but Dylan pays particular attention to the 1939 film adaptation, which includes a blackface performance by Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland.

Dylan describes America’s sweethearts “slapping on the blackface and mugging incessantly through a simulacrum of a traditional minstrel show, with Rooney portraying Mr. Bones, Garland portraying Mr. Tambo, and Douglas McPhail portraying the straight-man interlocutor. All three characters were minstrel show mainstays, which explains but does not excuse their presence” (332). He neglects to mention that Rooney and Garland’s grotesque travesty opens with a performance of Foster’s “Oh! Susanna.” The phrase “explains but does not excuse” applies to Foster’s troubling entanglement with minstrelsy in “Nelly Was a Lady” as well, and to some of Dylan’s own excursions into this cultural minefield.

Eric Lott devotes a chapter to Dylan in his 2017 book Black Mirror: The Cultural Contradictions of American Racism. Lott speculates, “I would guess that Dylan regards minstrelsy, say, whatever its ugliness, as responsible for some of the United States’ best music as well as much of its worst” (201). Lott further asserts that Dylan “wants to step up and face the racial facts of one of the traditions he inherited” (202).

Does Dylan “step up and face the racial facts” of “Nelly Was a Lady” in The Philosophy of Modern Song? Not exactly. He foregrounds the things he loves about the song while remaining largely silent about its more disturbing elements. That said, while hopscotching his way through Chapter 24, he purposefully drops tell-tale clues that point towards the skeletons in Foster’s walls. He draws circles around his own omissions and calls attention to things he avoids confronting directly—presumably so that annotators like me have something to do in newsletters like this. In his signature style for the book—the art of the unsaid—Dylan makes furtive glances and winking innuendos to insinuate connections between Foster, Poe, and his own work. Then he leaves the shadow chasing to us.

Works Cited

Dodd, David G. The Complete Annotated Grateful Dead Lyrics. Simon & Schuster, 2015.

---. “Hard Times.” Good as I Been to You. Columbia, 1992.

Dylan, Bob. “I Contain Multitudes.” Rough and Rowdy Ways. Columbia, 2020.

---. “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door.” Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid. Columbia, 1973.

---. “Love Minus Zero / No Limit.” Bringing It All Back Home. Columbia, 1965.

---. “Love and Theft.” Columbia, 2001.

---. “Nettie Moore.” Modern Times. Columbia, 2006.

---. The Philosophy of Modern Song. Simon & Schuster, 2022.

---. Time Out of Mind. Columbia, 1997.

Foster, Stephen C. “Camptown Races.” Songs of America. https://songofamerica.net/song/camptown-races/.

---. “Nelly Was a Lady.” Songs of America. https://songofamerica.net/song/nelly-was-a-lady/.

---. “Oh! Susanna.” Songs of America. https://songofamerica.net/song/oh-susanna/.

Herren, Graley. Dreams and Dialogues in Dylan’s Time Out of Mind. Anthem Press, 2021.

Hilburn, Robert. “Rock’s Enigmatic Poet Opens a Long-Private Door.” Los Angeles Times (4 April 2004). Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances. Ed. Artur Jarosinski. Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006, pp. 1337-43.

Lott, Eric. Black Mirror: The Cultural Contradictions of American Racism. Belknap Press, 2017.

---. Love & Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class. Oxford University Press, 1993.

Masked and Anonymous. Directed by Larry Charles. Written by Sergei Petrov and Rene Fontaine (aka Bob Dylan and Larry Charles). Sony Pictures Classics, 2003.

Poe, Edgar Allan. “The Philosophy of Composition.” Poetry Foundation. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/69390/the-philosophy-of-composition.

---. “The Raven.” Poetry Foundation. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/48860/the-raven.

Reginio, Robert. “‘Nettie Moore’: Minstrelsy and the Cultural Economy of Race in Bob Dylan’s Late Albums.” Highway 61 Revisited: Bob Dylan’s Road from Minnesota to the World. Eds. Colleen J. Sheehy and Thomas Swiss. University of Minnesota Press, 2009, pp. 213-24.

Slate, Jeff. “Bob Dylan Q&A about ‘The Philosophy of Modern Song’” (20 December 2022). The Official Website of Bob Dylan. https://www.bobdylan.com/news/bob-dylan-interviewed-by-wall-street-journals-jeff-slate/.

Great digging and beautifully illuminated. If I were in Tulsa, I’d try to connect with you in person Graley, to get your perspective on this: I’m not sure that Bob’s fascination with minstrelsy has dwindled. To your examples from TPOMS we can add a central image from Rough and Rowdy Ways. As I’ve written about in my book, serialized here on Substack, the phrase “I don’t love nobody,” from “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)” is a minstrel tune written by Lew Sully. The original lyrics and performances in blackface are unquestionably racist and disturbing. But the most famous version of the song was released by Libba Cotten on her late 1950s album recorded by Dylan’s inspiration, Mike Seeger, who is also alluded to in “Key West” in the opening, as one of the New Lost City Ramblers, who recorded a version of Charlie Poole’s “White House Blues.” So it’s easy to imagine Bob has both Sully’s and Cotten’s versions of “I Don’t Love Nobody” in mind when he cites it in the penultimate verse. Why are these references included? In my view, it’s because the great Soul, Elizabeth Cotten, has redeemed the song from its unholy, yet musically fascinating past. And “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)” is a song all about redemptions and confessions at the edge of heaven. As you point out so beautifully, Dylan is working all kinds of magic below the surface. Check out my book for more.

This a great analysis, but I think I just heard a similar paper at the World of Bob Dylan Conference in Tulsa by a person purporting to be “Graley Herren”. Do you care to explain the “coincidence?”