The Mysterious Bert Cartwright

The Story Behind "The Mysterious Norman Raeben" & Its Author

Next week is the World of Bob Dylan 2025 conference in Tulsa. It promises to be a huge extravaganza, with panel presentations by scholars and fans, round-table discussions, film screenings, keynote addresses by prominent speakers, a new exhibit on Going Electric at the Dylan Center, and a plugged-in hootenanny at Cain’s Ballroom celebrating Dylan’s songs from 1965. I hope to see some of you there.

I’ll be moderating a panel on the 50th anniversary of Blood on the Tracks. I’m honored to be joined by the Queen of Dylan podcasters, Laura Tenschert, and the King of Dylan Substackers, Ray Padgett. My paper is about Norman Raeben’s influence on Dylan. This is an updated version of the piece posted here several months ago. Today I want to take you down an adjacent rabbit hole I discovered during my research. None of this will be included in my Tulsa presentation. “The Mysterious Bert Cartwright” is an exclusive bonus for Shadow Chasing readers.

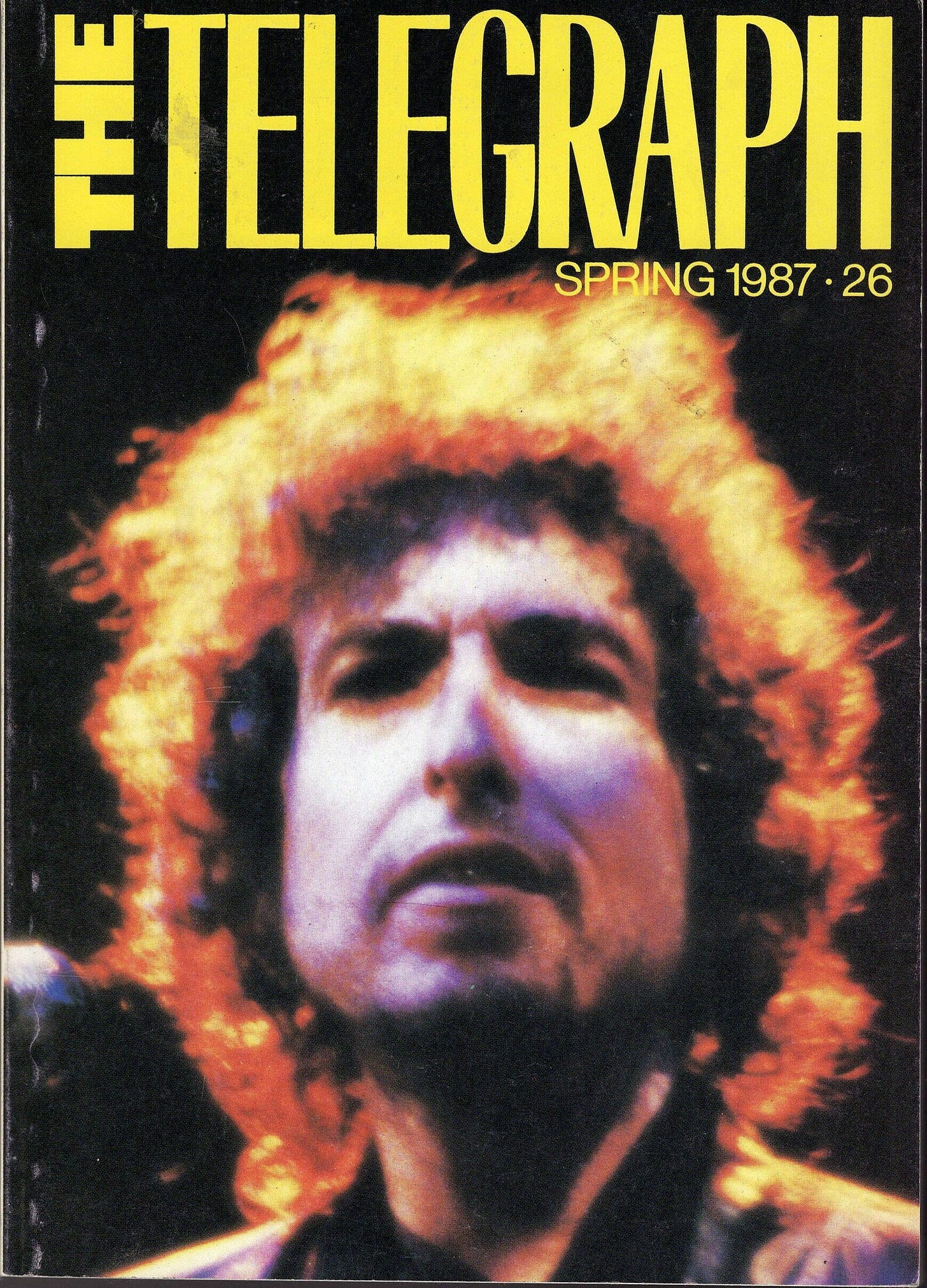

Anyone studying the Dylan-Raeben connection is indebted to the research of Bert Cartwright. He published an article in the Spring 1987 issue of John Bauldie’s fanzine The Telegraph titled “Dylan’s Mysterious Man Called Norman Raeben.” In 1990, Bauldie reprinted it as a chapter in his collection Wanted Man: In Search of Bob Dylan, truncating the title to “The Mysterious Norman Raeben.” Pretty much everything written on the subject since then, including my own modest efforts, have been footnotes to Cartwright’s groundbreaking work.

While working on my earlier Shadow Chasing piece about Raeben, I stumbled across a database entry on the Colbert Cartwright Collection of Bob Dylan Recordings and Research Files at Bowling Green State University, located a few hours north of Cincinnati. I recently struck up a correspondence with Angela Pratesi, Head Librarian at BGSU’s Music Library. She kindly granted me access to Cartwright’s research files for “The Mysterious Norman Raeben,” and she has given me permission to share some of the documents housed there.

The more I looked through Cartwright’s files, the more interested I became in the researcher himself. It turns out that he was much more than a first wave Dylanologist. I first learned about his fascinating backstory from Michael Gray in The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia, and I uncovered even more while working on this piece. Before we peek behind the veil of “The Mysterious Norman Raeben,” let’s first learn some more about the mysterious Bert Cartwright.

Reverend Cartwright: Civil Rights Advocate

Colbert Scott Cartwright was born in 1924 in Coffeyville, Kansas. He was the son of Rev. Lin Cartwright, pastor of the First Christian Church. The elder Cartwright was deeply opposed to racism and policies of racial discrimination in Kansas, where he had several clashes with the local Ku Klux Klan. He moved the family to Chattanooga, Tennessee, in the thirties and headed up the city’s interracial council. The family then relocated to St. Louis, Missouri, where young Bert earned a bachelor of arts degree from Washington University in 1946.

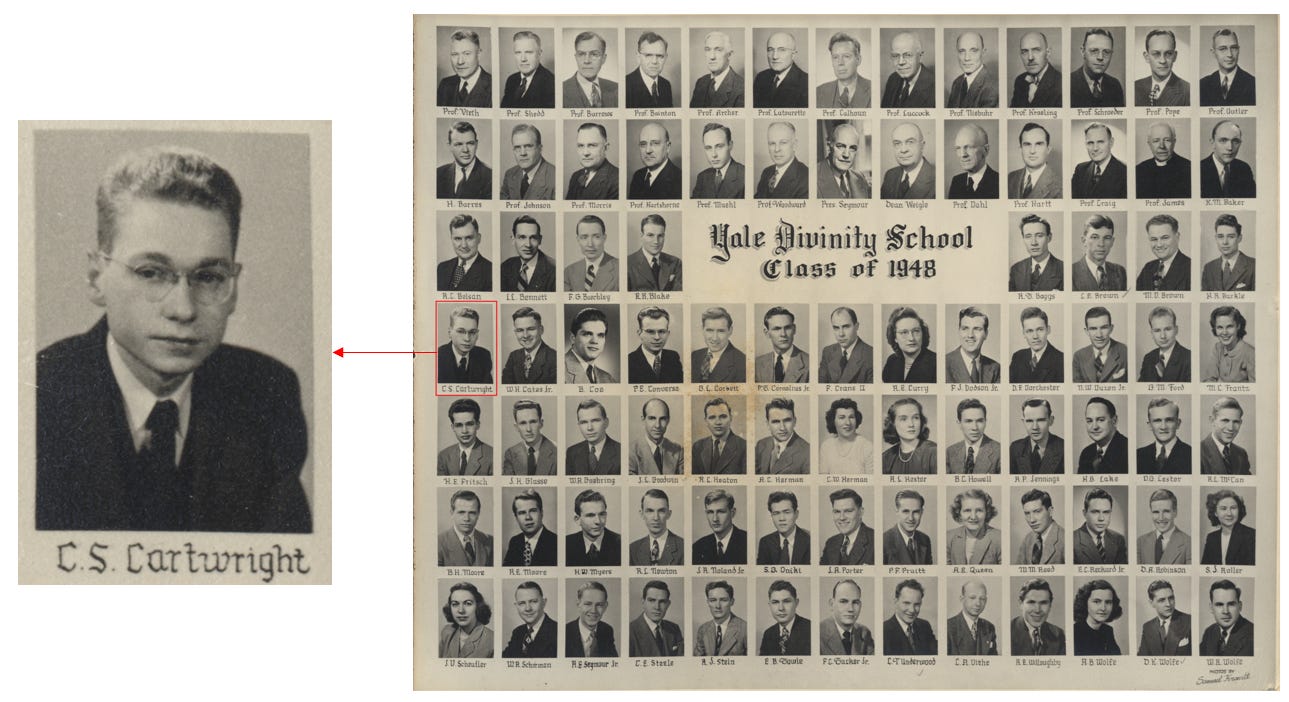

Wishing to follow his father into the ministry, Cartwright enrolled in Yale Divinity School, where he earned a bachelor of divinity degree in 1948 and master of sacred theology degree in 1950.

During his long and distinguished career, he served as pastor in Lynchburg, Virginia (1950-53); Little Rock, Arkansas (1954-64); Youngstown, Ohio (1964-70); Fort Worth, Texas (1971-79); and the Trinity-Brazos area of the Southwest (1979-89). He wrote multiple books about the history, practices, and faith of his denomination the Disciples of Christ. He received an honorary doctorate of divinity from Texas Christian University in 1976. Cartwright retired from preaching in 1989 and died in 1996. The following year, he was posthumously honored with the Christian Board of Publication’s Chalice Lifetime Achievement Award.

Principled confrontation with institutional racism was a family tradition among the Cartwrights. During his first post in Lynchburg, Bert Cartwright was elected chair of an interracial Christian youth group, landing him in hot water with segregationists in the area. Later in his career, he led the Youngstown Human Relations Committee, where he fought against racial discrimination in local housing. His most active involvement in the civil rights movement came during the fifties as pastor of Pulaski Heights Christian Church in Little Rock.

With its 1954 landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that racially segregated schools were unconstitutional and ordered the desegregation of American schools “with all deliberate speed.” Many political and educational leaders in the South resisted this court order. Black students attempting to enroll in previously all-white schools became targets of virulent abuse by segregationists opposed to mixing the races.

One of the most notorious flashpoints occurred on September 4, 1957, when nine Black students tried to attend their first day of classes at Central High School in Little Rock. Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus called out the state’s National Guard to try and prevent desegregation of the school, prompting President Eisenhower to deploy federal troops to enforce the rule of law. An angry white mob surrounded the school to protest the admission of the so-called “Little Rock Nine.” An iconic photo of Elizabeth Eckford being showered with hatred just for trying to go to school became emblematic of Southern racism during the Jim Crow era:

The night before this showdown at Central High, Daisy Bates, head of the Arkansas NAACP, reached out for help from Dunbar Ogden, president of the Little Rock Interracial Ministerial Alliance. According to the Encyclopedia of Arkansas, Bates asked Ogden “to gather a group of white ministers who would accompany the Little Rock Nine as they sought to enter the school. Ogden agreed to try, but after calling about a dozen of those he thought most likely to join, only one, Colbert Cartwright, agreed to go.”

The following Sunday, the normally soft-spoken pastor delivered a fiery sermon from the pulpit of Pulaski Heights Christian Church, praising the Christian courage of the students and deploring the wicked bigotry of the white mob. In a profile for the Arkansas Times called “A Reluctant Hero,” Roy Reed writes,

Bert Cartwright’s sermon the next Sunday was a stark description of Eckford’s trial as he watched it unfold in front of Central High School. He quoted the psalms she had read before leaving home to face the hostile crowd. He spoke of her dream of becoming a lawyer. He spoke of visiting in her home and of his shame, that week, at being white. Then he declared that the nine black students who were trying to get to Central High were human beings, and that white people who lost sight of that were in danger of losing their own souls. Eckford, he said, “has more guts than anyone present here today.”

David Andrew Lai describes the repercussions of this sermon in his study Up in the Balcony: White Religious Leaders and School Desegregation in Arkansas, 1954-1960:

Even though Pulaski Heights was a remarkably progressive church that had supported pastors criticizing internment [of Japanese Americans during World War II] and respected the freedom of the pulpit, the 8 September sermon triggered a minor schism that ultimately resulted in thirty members, about a tenth of his congregation, leaving Pulaski Heights. (74)

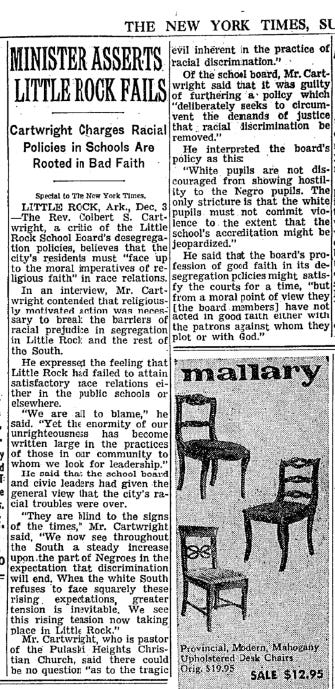

Even after the Little Rock School Board reluctantly began to integrate, Cartwright remained a persistent thorn in their side for years, protesting the unequal treatment of Black students in the school system. He even attracted the attention of the New York Times, which ran a piece on Cartwright in December 1960. The article opens:

The Rev. Colbert S. Cartwright, a critic of the Little Rock School Board’s desegregation policies, believes that the city’s residents “must face up to the moral imperatives of religious faith” in race relations. In an interview, Mr. Cartwright contended that religiously motivated action was necessary to break the barriers of racial prejudice in segregation in Little Rock and the rest of the South.

Cartwright told the reporter, “‘We are all to blame. Yet the enormity of our unrighteousness has become written large in the practices of those in our community to whom we look for leadership.’” He accused segregationists of being “‘blind to the signs of the times.’” The preacher denounced the actions (and inactions) of the Little Rock School Board members as morally reprehensible: “‘from a moral point of view they have not acted in good faith either with the patrons against whom they plot or with God.’”

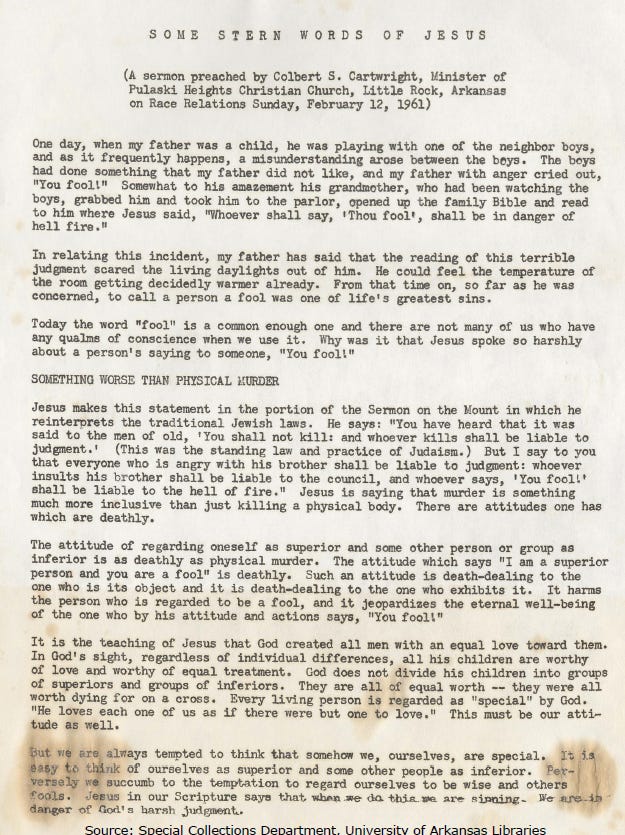

A couple months after this article appeared in the New York Times, Cartwright delivered another incendiary sermon at Pulaski Heights. His message to the congregation on February 12, 1961—around the time Dylan was composing “Song to Woody”—was titled “Some Stern Words of Jesus.” I found a copy from Special Collections at the University of Arkansas Library. Here is the first page:

Cartwright uses passages from the Sermon on the Mount to show how Jesus’ message is incompatible with racial discrimination. He concludes with this provocation:

Jesus drops a bomb in the midst of our complacency, saying “Don’t go to church again until you correct your offense against your Negro brother.” It’s just that urgent. Well, I don’t suppose any of us are going to take Jesus that seriously, but he does shatter our complacency. He reminds us that we don’t have forever to work this problem out. The time to do something is NOW.

The civil rights struggle took a heavy toll on Cartwright, personally and spiritually. Looking back on his activism, he was skeptical about his accomplishments. He offered this harsh self-assessment in his 1993 autobiography Walking My Lonesome Valley:

I determined to work within the church and culture to transform it in companionship with Christ who had not given up on either. At some points I turned to secular political expediencies of the moment, counseling a school board how to survive by a minimal compliance with the Supreme Court school decision. Disillusioned with this approach, I turned prophet, attacking those who had generally followed my counsel. In the end I tended to conclude that attempts to work with Christ to transform the church and society were not adequate. (qtd. Lai 122)

Speaking with Roy Reed in 1990, the year after he retired from the ministry, he frankly admitted, “‘My whole self-understanding of the church and the world and God was shaken. I don’t think I got to the point of no hope, but diminished expectations.’”

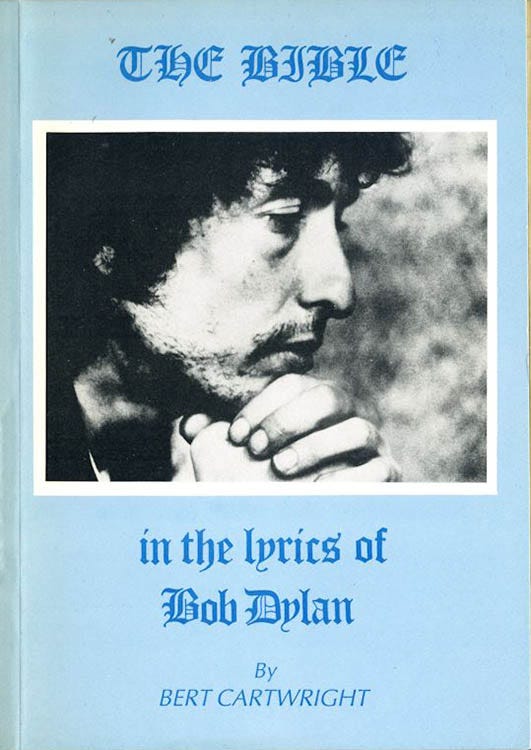

Fortunately for Cartwright—and for us—around the time that his faith was at low ebb, he was buoyed up by a passion for the songs of Bob Dylan. Among his new congregation (the Disciples of Bob?), he is best known for two works. The first is The Bible in the Lyrics of Bob Dylan, published in 1985 as part of John Bauldie’s Wanted Man series, and later reissued in an expanded second edition in 1992. The other is “The Mysterious Norman Raeben.”

The Norman Conquest

What follows is a kind of meta-criticism. I’m doing research —> into Cartwright’s research —> about Dylan’s art —> influenced by Raeben’s teaching. It’s also a celebration of the delights of archival scavenger hunting, shuffling papers like treasure maps in search of hidden gems. There aren’t many audiences who would care about such esoterica, but I hope readers of this site will dig it as much as I do. Now let’s chase some shadows!

We’ll pick up the trail in December 1985, when Cartwright submitted a new manuscript to The Telegraph.

In the cover letter Cartwright told Bauldie, “I am enclosing an article on the influence of Norman upon Dylan. I do think I make the case for the importance of the subject. The material from a Dallas interview [by Pete Oppel of the Dallas Morning News] is undoubtedly fresh to most readers as I include that among other more familiar materials” (Cartwright to Bauldie, 7 December 1985).

Cartwright referred to his subject as “Norman” because he still didn’t know the man’s full name. Dylan had made oblique references to an influential art teacher in multiple interviews but intentionally withheld the name in order to protect his mentor’s privacy. The closest he came to revealing Raeben’s identity came in the 1977 Playboy interview with Ron Rosenbaum:

Just an old man. His name wouldn’t mean anything to you. He came to this country from Russia in the twenties, started out as a boxer and ended up painting portraits of women. […] His first name was Norman. Every time I mention somebody’s name, it’s like they get a tremendous amount of distraction and irrelevancy in their lives. (547)

Cartwright kept running into dead-ends in his search for the shadowy figure. He told Bauldie, “I have tried to track down who Norman is and thought I had identified him, but when contacted it clearly was not the right person. This article could possibly help turn up the right person—though if he is living I think we would not want to publish the name” (Cartwright to Bauldie, 7 December 1985).

Bauldie replied to Cartwright in February 1986, encouraging him to continue his detective work and giving him a possible new clue. “You may be interested in the enclosed note from Jonathan Cott. It’s a shame he lost the details” (Bauldie to Cartwright, 5 February 1986).

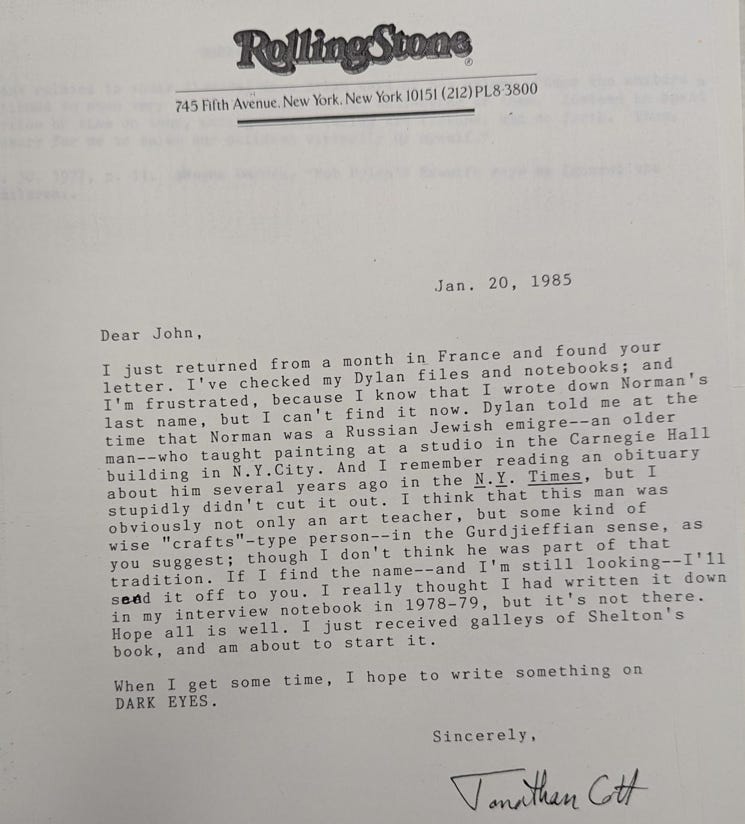

You’ll recognize Cott as the Rolling Stone journalist who conducted a series of probing interviews with Dylan in the late seventies. Bauldie specifically asked him the name of Dylan’s art teacher, and Cott replied:

I’ve checked my Dylan files and notebooks; and I’m frustrated, because I know that I wrote down Norman’s last name, but I can’t find it now. Dylan told me at the time that Norman was a Russian Jewish emigre—an older man—who taught painting at a studio in the Carnegie Hall building in N.Y.City. And I remember reading an obituary about him several years ago in the N. Y. Times, but I stupidly didn’t cut it out. I think that this man was obviously not only an art teacher, but some kind of wise “crafts”-type person—in the Gurdjieffian sense, as you suggest; though I don’t think he was part of that tradition. If I find the name—and I’m still looking—I’ll send it off to you. I really thought I had written it down in my interview notebook in 1978-79, but it’s not there. (Cott to Bauldie, 20 January 1985)

As a side note, isn’t it cool to read the personal correspondence of writers you’re familiar with, especially when they share the same forehead-smacking frustrations we all experience during the writing process?

Eureka! Cott’s recollection of the art studio’s location was the key that unlocked the mystery. Cartwright shared this detail with his friend Dalton Delan. Delan went on to become a writer and TV executive, and he was executive producer of the program at the White House where Dylan played for President Obama.

But in 1986, Delan was an enthusiastic Dylan fan on a sleuthing expedition. Using letterhead from his workplace at ABC News, Delan excitedly wrote Cartwright: “Well, we finally hit the jackpot! Thanks to your info re Carnegie Hall, I did some sleuthing on this end and hit it! His name was: NORMAN RAEBEN” (Delan to Cartwright, 12 June 1986). Delan also passed along the addresses and phone numbers for Raeben’s son Jay and his widow Victoria.

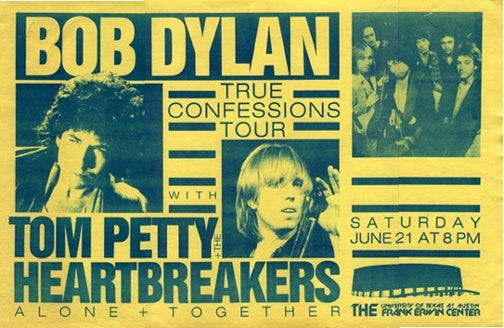

In closing, he proposed a barter: “Perhaps in return for my spadework you could send me dubs of the Houston 6/20, Austin 6/21 and Dallas 6/22 concerts if you attend any/all of them?” (Delan to Cartwright, 12 June 1986). Love it! Research assistance in exchange for bootleg tapes from the True Confessions Tour with Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers. That’s some old school Dylanology right there.

Cartwright’s response the following month was effusive: “WOW!!! The material you sent is fascinating, not only for the additional information there is, but to see how a taped interview gets translated into a printed one” (Cartwright to Delan, 26 July 1986). [Much more on that last comment in a moment.] Cartwright told Delan that he tried calling Victoria Raeben and finally reached her:

She was so shocked by my phone call that I could only get permission to call at another time. It was apparent that no one had ever called her about the topic of Dylan and she had never thought about doing any kind of an interview. After several no answers during the week I finally got through to her this afternoon. She was still jittery about it and found it difficult to understand clearly what my purpose in calling was. I am enclosing a copy of the tape I made. (Cartwright to Delan, 26 July 1986)

The online description of the Cartwright Collection says that it contains a transcript of his interview with Victoria Raeben. That teaser motivated me to contact the library in the first place. Having read the brief transcript of their conversation, however, I must report that Cartwright’s description to Delan is accurate: there really isn’t much there. She was clearly caught off guard. She distrusted this stranger who cold-called her with a bunch of questions, and she was very guarded with her responses, uncertain of the interviewer’s agenda. She did mention that Dylan visited her and Norman at their house a couple times, possibly to play chess, which I hadn’t heard before. But that’s about the only revelation to be found in Cartwright’s phone interview with Victoria Raeben. That’s the bad news. The good news is that there is a much more interesting interview transcript on file in the Colbert Collection.

As you may recall, I used the subtitle “Don’t Draw the Vase” for my previous piece about Raeben’s influence on Dylan. That’s a reference to this colorful anecdote in Cartwright’s article where Dylan recalls his first meeting with the enigmatic art teacher:

He says, “You wanna paint?” So I said, “Well, I was thinking about it, you know.” He said, “Well, I don’t know if you even deserve to be here. Let me see what you can do.” So he put this vase in front of me, and he says, “You see this vase?” And he put it there for 30 seconds or so, and then he took it away and he said, “Draw it.” Well, I mean, I started drawing it and I couldn’t remember shit about this vase—I’d looked at it but I didn’t see it. And he took a look at what I drew and he said, “OK, you can be up here.” And he told me 13 paints to get. Well, I hadn’t gone up there to paint, I’d just gone up there to see what was going on. I wound up staying there for maybe two months. This guy was amazing. (qtd. Cartwright 85-86)

I love this story, but I was disappointed to find that Cartwright failed to cite his source in the article. He’s usually pretty scrupulous about that sort of thing, so I figured it was just a rare proofreading lapse. But then I started doing keyword searches through the various published interviews with Cartwright references, and none of them contain this story. I looked in my go-to source for Dylan interviews, Artur Jarosinski’s Every Mind Polluting Word, and still nothing. Google search: nada. Where did this quotation come from, and why didn’t Cartwright cite it?

Mystery solved! “The material you sent is fascinating, not only for the additional information there is, but to see how a taped interview gets translated into a printed one” (Cartwright to Delan, 26 July 1986). Among the items Delan sent to Cartwright was a transcript of a redacted portion of Jonathan Cott’s 1978 interview with Dylan. We know that Dylan wanted to guard Raeben’s privacy. He apparently asked Cott not to include part of their discussion where he revealed his teacher’s identity and elaborated upon his time studying with Raeben.

The story about Dylan drawing the vase can be found in a 14-page double-spaced interview transcript in Cartwright’s research folder on Raeben. It is untitled and unattributed. The conversation picks up in media res, with the interviewer labeled “Q” and the interviewee labeled “A.” But it’s clear from internal evidence in Cartwright’s correspondence that the source is Cott’s two-part 1978 interview with Dylan—a redacted section not authorized for publication.

Cartwright was on the horns of a dilemma when he wrote to Delan: “I shall hold up on any decision as to the appropriate use of the transcript. I am aware of the sensitivity of the matter and I have no desire to put either Cott or you in a hot spot” (Cartwright to Delan, 26 July 1986). As a Christian preacher, Cartwright had scruples over violating Dylan’s wishes and exposing Cott, Delan, Bauldie, and himself to the man’s wrath, let alone his litigation. But as a Dylanologist, he simply couldn’t pass on such a juicy scoop.

Remember that, in his initial letter to Bauldie, Cartwright wrote, “This article could possibly help turn up the right person—though if he is living I think we would not want to publish the name” (Cartwright to Bauldie, 7 December 1985). Once he learned that Raeben died in 1978, it was full steam ahead on revealing the teacher’s identity. Cartwright led with his discovery by titling the piece “Dylan’s Mysterious Man Called Norman Raeben.” He also incorporated details about the artist’s background from the redacted portion of Cott’s interview. And he couldn’t resist sneaking in the (uncited) quote about Dylan and Raeben’s origin story.

Bauldie was privy to this cloak-and-dagger business. In Cartwright’s cover letter accompanying the revised final draft, he wrote, “I was able to smuggle some of the Cott interview in without jeopardizing the source. The sleuth that you are, I am sure you will spot the attempts!” (Cartwright to Bauldie, 1 February 1987). Bauldie knew that his readers would gobble up this feast of new revelations, so he featured the article in the very next issue of The Telegraph.

Cott’s 1978 Interview with Dylan – Unredacted

At the beginning of the excerpt, Cott and Dylan were talking about names.

Q: Could you have been successful as Zimmerman, do you suppose, doing what you’re doing now? Obviously, I’m sure you could have been.

A: Well, I don’t know. It never occurred to me. I don’t know. These names we have down here aren’t really our true names anyway.

Q: What are our true names?

A: Well, we find out when we get into the other world, what our true names are and who we really are.

This issue of true identity prompted Dylan to introduce his art teacher by name into the discussion:

I used to have this painting instructor, this guy who was Sholom [sic] Aleichem’s son. Ever heard of Sholom Aleichem? He was a writer; ‘Fiddler on the Roof’ and that stuff? I mean, I hate that kinda thing. […] But, anyway, his son—his name was Rabinowitz, Norman Rabinowitz—and this guy was one of the great geniuses of all time, really. He was 86 years old when I met him. I met him, he used to teach painting class upstairs on the eleventh floor of Carnegie Hall.

It’s interesting that he explicitly identified his teacher and used his original Ukrainian surname. Just to set the record straight, Raeben was only 72 years old when Dylan studied with him, not 86. As you can see, Dylan rated Raeben’s art and teaching much more highly than the “sentimental, wishy-washy” literature of Aleichem’s Fiddler on the Roof and Singer’s Yentl:

Friends of Sara told him about this teacher and suggested that he look Raeben up the next time he was in New York. He visited the studio and was surprised by the diverse roster of students: “I walked into his class and it was amazing. He had anywhere from twelve to twenty people up there. And they were all kinds of people. He had a off-duty policeman to investment counselors to old women from Florida to young art student rejects, stuff like that.” I love the way Dylan described Raeben’s imposing presence in the classroom:

He knew every political . . . every political game you can imagine. He knew every religious game. He knew science, he knew archaeology, he spoke eight languages. Eighty-six years old, he used to sit there in a T-shirt like Marlon Brando, and a big heavy-set guy, and he was writing a dictionary at this time.

As you can see, this is also the portion of the interview where Dylan told the story about drawing a vase for his entrance exam into Raeben’s class.

The “dictionary” referred to here was a book on aesthetics that Raeben and his wife Vicki were working on. In her phone interview with Cartwright, she told him, “He was writing a book on art in collaboration with me and we had the first chapter accepted by Doubleday, but he died, yk, before we got it written” (Victoria Raeben to Bert Cartwright, 26 July 1986). [Note that “yk” is an abbreviation for “you know” throughout these transcripts.] You can read a few of Raeben’s lectures as appendices in Carolyn Schlam’s excellent book The Creative Path.

Dylan wasn’t merely impressed with Raeben as an art teacher. He was also astonished by the man’s deep insights into his pupils’ lives.

And he’d make the rounds. And he’d see what you were doing and he’d walk up to people, walk up to a person, you’d hear him say, a little old man who’s painting this, he’d walk up to him and says, “You’re an adulterer,” yk. And he would expound on why this man is an adulterer. And then he’d walk up to somebody else and say, “You’re just living a world of fantasy.” And I’ve seen big, tough, grown men just cry, and leave the class. I saw people who came and thought they were the next Picasso, right outta art school, yk, who’d come in there, who couldn’t see what was in front of ’em.

What did Raeben see when he peered into Dylan? “I mean, the first time he looked at me he said, ‘Oh, you’re an Italian Jew.’ And he says, ‘You’re an Italian Jew from the year 1100.’ I said, ‘Oh? I’ve always wanted to know who I am, yk.’ But he said this about everybody.”

What did Raeben see when he looked at Dylan’s art? Not much that he liked. You may have heard rumors that Raeben called Dylan an “idiot” in class, and that Dylan borrowed this insult for “Idiot Wind” on Blood on the Tracks, the album he wrote and recorded in the months following his classes with Raeben. The unredacted transcript confirms it: “And one of the things which I learned or which came outta that actually was that term . . . that song ‘Idiot Wind.’ ’Cause up until that time, it was like somebody call somebody an idiot, it was like a bad thing. But in his world, everybody was an idiot. And he was right, yk.”

The transcript also sheds potential light on another Blood on the Tracks rumor, this one started by Dylan himself. In the “New Morning” chapter of Chronicles, he describes his ongoing cat-and-mouse game with critics who persistently misinterpret his work. Dylan claims, “Eventually I would even record an entire album based on Chekhov’s short stories—critics thought it was autobiographical—that was fine” (122). Good luck trying to convince readers and listeners that Blood on the Tracks is inspired by Chekhov’s fiction rather than the breakup of Dylan’s marriage. However, the unredacted interview reveals where that cover story might have come from. Dylan told Cott that Raeben would sometimes bring literature into the studio, read passages aloud, and offer running commentary. Then he shared this tantalizing anecdote: “Evidently, when his father was dying, his father wanted to hear Chekov short stories, so he’d read Chekov short stories to his father on his death bed.” So there it is: Fiddler on the Tracks.

One thing that comes through clearly in this transcript is Dylan’s deep commitment to painting. This was not just some temporary hobby. In fact, he put his passion for painting on more or less equal footing with music:

But painting and music has always sorta gone side by side with me. I’ve never been able to really give the time that I’ve wanted to to painting. But I’ve always wanted to. I can’t say I really love it any less than music. I just don’t . . . Actually, I could. I mean, it’s not as immediate as picking up a guitar and hearing a chord. But there’s somethin about making somethin on a canvas which is alive. Most stuff you see isn’t alive; it’s dead, dead art.

Raeben was doubtful about Dylan’s talent as a painter, and the pupil took this criticism to heart:

He said, “You’re not ready yet to draw a model. You can’t see that model. And you can’t even draw that flower there. You could draw it, but you can’t see the color in it. You don’t know how to apply your paint, anyway.” He was right. I didn’t know how to apply paint. He showed me how to apply paint. But that even, I’m not an expert at it. That’s a whole different school. I mean, you could spend years just figuring out how to get colors. I didn’t do that either.

Reflecting upon his limitations led Dylan to make some very perceptive insights into his own work. For instance, here is one of my favorite observations in the entire transcript:

My stuff was just force of . . . of feeling. Yeah, that’s another thing he said was “Feeling and technique.” I had a lot of feeling; very little technique. Probably the same thing in my music.

What an honest self-assessment of Dylan’s art as both painter and musician: tremendous force of feeling, but erratic discipline when it comes to technique.

Speaking of techniques, have you heard about Dylan’s box? Larry Charles, the director and co-writer of Masked and Anonymous, has spoken about a special box of scribbles that Dylan used for inspiration. Charles explained the function of the box to Brett Arnold of Business Insider:

He brings out this very ornate beautiful box, like a sorcerer would, and he opens the box and dumps all these pieces of scrap paper on the table . . . and yes, that is exactly what he does . . . every piece of scrap paper was a hotel stationery, little scraps from Norway and from Belgium and Brazil and places like that, and each little piece of paper had a line, like some kind of little line scribbled or a name scribbled, “Uncle Sweetheart,” or a weird poetic line or an idea or whatever […]. I realized that’s how he writes songs, he takes these scraps and he puts them together and makes his poetry out of that.

Raeben used a comparable box of inspiration, only his box contained images instead of words. Dylan told Cott: “He had a big box, those cardboard boxes, filled with photographs. He’d take a photograph out, a prize-winning photograph, and he’d say—most of it was all black and white stuff—and he’d take one out and say . . . This guy would talk from eight in the morning until four. There was never a moment when he didn’t talk.”

Dylan vividly recalled Raeben’s box because it was the source of his one and only successful painting under the master’s tutelage. You can practically hear the excitement in Dylan’s voice as he recounted this experience to Cott:

A: I remember I did this painting of a guy that he showed me. There’s this guy just lookin into the camera, taken maybe 1930. Very fierce lookin, serious lookin guy. […] This was only my third or fourth day there. And then he said, “Do this one. This is on your level. Do that one. You shouldn’t have any trouble with this. Do this.” And I did it and I couldn’t believe it. I couldn’t believe I did it.

Q: It worked?

A: Yeah! I mean, it worked. I couldn’t believe that I did it. I felt nervous while I was doing it, but yet I did it. And there it was. And he came by and he looked at it and his eyes just popped out of his head just about. And he said, “Yeah, that’s it.” And he took it and he hung it up. And that was all. But that’s the last time he ever did that. Other than that . . . that’s the only . . . That’s the only thing I ever completed in that class. Most times, you just did somethin and he wiped your canvas off the next day—scraped your painting right off.

Cott asked what happened with the painting, and Dylan said he got Raeben’s permission to keep it after his final class. He was living in the Village at the time, and he tells an interesting story about taking the canvas home:

A: I took it on the subway, I took it back downtown. I still had that house on MacDougal Street at that time. And I had it, I was sittin there with it on the subway. And people would not look at it. They’d look at it and their faces would just go . . . just uh . . . It was like it would move ’em back, yk.

Q: A disturbing painting?

A: No, I don’t think it was. But like he said, whatever it was, I had gotten whatever there was to get out of it.

It’s nice to know that Dylan had one successful memento from his time studying with Raeben. I sure wish we could see that painting, don’t you? As for the startled reaction of his fellow passengers, surely it had something to do with the sudden realization that they were riding the downtown train with Bob Dylan!

On the final page of the transcript, Dylan summed up his mind-blowing experience of studying with Raeben:

But it was like being on acid, going to that class. It was like being on acid because you saw so much, you couldn’t see. I mean, you’d go out . . . This man did not like to look at Nature. It was too much for him, yk. See, on his level you could rebend shapes. Me, I’m not gonna do that. He could see behind things. Just like Picasso could, and Braques [sic]. I mean, you get on that level, you can’t deal with other people. You don’t even want to, yk.

Before shifting back to musical matters—and going back on the record—Cott asked Dylan a final question about painting: “Have you painted your masterpiece yet?” Dylan replied, “I hope I never do. I hope I never do.”

Archival Dylan Studies

I’m surprised by Bert Cartwright’s restraint in using so little of this revelatory 14-page excerpt from the Cott interview. I suppose he was wary of drawing too much attention to this unauthorized source. But I’m thankful that he saved a copy for posterity so that you and I could take several more bites of the forbidden fruit.

Archival research has enormous potential for future scholarship in our field. The stewards of that privileged material must treat it conscientiously, with an eye toward open access in the best interests of Dylan Studies. I’m aware of a case recently where a scholar who studied at the Bob Dylan Archive in Tulsa submitted an article to The Dylan Review but was denied permission to quote from any of the archival manuscripts. I’m not sure who wielded the axe on behalf of the estate, but it’s a worrisome sign. Call me naïve, but I don’t see the point in having an archive at all if you don’t let researchers share what they discover there.

Angela Pratesi and the Special Collections folks at BGSU have been a model of collegiality and openness. I wouldn’t have gained access to Cartwright’ files without her help, and I couldn’t have passed along what I learned without her generous permission. This is how research should work.

Scholars have the opportunity to learn so much more about Dylan’s art from his archival material. Allowing us to share our findings is for the greater good of Dylan Studies, and it helps to ensure that the artist’s legacy will continue to thrive. I urge the Dylan estate to foster an open-door policy that encourages and facilitates archival research, rather than using their gatekeeping authority to slam the door shut. Thanks to the Cartwright Collection and the BGSU librarians, I’m happy to have opened some doors for you into the mysterious Bert Cartwright and his research on “The Mysterious Norman Raeben.”

Works Cited

Arnold, Brett. “HBO Producer Reveals the Crazy Story of When Bob Dylan Tried to Make a TV Show.” Business Insider (10 November 2014), https://www.businessinsider.com/bob-dylan-almost-made-an-hbo-slapstick-comedy-with-a-seinfeld-writer-2014-11.

Cartwright, Bert. “The Mysterious Norman Raeben.” Wanted Man: In Search of Bob Dylan. Ed. John Bauldie. Citadel Press, 1990, 85-90.

Cartwright, Colbert S. “Some Stern Words of Jesus.” Pulaski Heights Christian Church, Little Rock, Arkansas (12 February 1961). Special Collections, University of Arkansas Libraries.

Colbert Cartwright Collection of Bob Dylan Recordings and Research Files. MUSIC 039, Box 17, Folder 2. Music Library and Bill Schurk Sound Archives, Bowling Green State University.

Cott, Jonathan. “The Rolling Stone Interview, Part 2.” Rolling Stone (16 November 1978). Rpt. in Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances. Ed. Artur Jarosinski. Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006, 668-78.

“Dunbar H. Ogden Jr. (1902-1978).” Encyclopedia of Arkansas, https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/dunbar-h-ogden-jr-13204/.Dylan, Bob. Chronicles, Volume One. Simon & Schuster, 2004.

Lai, David Andrew. Up in the Balcony: White Religious Leaders and School Desegregation in Arkansas, 1954-1960. Master’s Thesis. University of Kentucky, 2012.

“Minister Asserts Little Rock Fails: Cartwright Charges Racial Policies in Schools Are Rooted in Bad Faith.” New York Times (4 December 1960), https://www.nytimes.com/1960/12/04/archives/minister-asserts-little-rock-fails-cartwright-charges-racial.html.

Reed, Roy. “A Reluctant Hero.” Arkansas Times (2 November 2017), https://arktimes.com/news/cover-stories/2017/11/02/a-reluctant-hero.

Rosenbaum, Ron. “Playboy Interview with Bob Dylan: A Candid Conversation with the Visionary Whose Songs Changed the Times.” Playboy (March 1978). Rpt. in Every Mind Polluting Word: Assorted Bob Dylan Utterances. Ed. Artur Jarosinski. Don’t Ya Tell Henry, 2006, 534-55.

Very important work. You've produced another article that is just indispenible as we continue to think about Dylan and his art. The Book Club just did a session on John Bauldie, so it was great to see his work pop up here, as well. One of the traits that puts you in the top tier of Dylanologists is the thoroughness and painstakingness of your research.

Great stuff. Great research. As a teenager, I loved those Jonathan Cott interviews in RS, they showed that Dylan was working with ideas way beyond any other musical artist. Mostly the conversation was about Street Legal and Renaldo and Clara, some very mystical and intellectual stuff, Cott was a great interviewer. (His book about children’s lit is fascinating.) Seems like Bob was still working through the ideas he got from studying under Raeben a few years earlier. We know where he went from there. He lost his mind! And found Jesus. Reading this, and Padgett’s recent interviews about Shadow Kingdom, show how much is factually hidden from our first takes on Dylan’s music. And he wants it to stay secret, at least for a while. It’s cool to find all this out later but I’m also remembering that the 16 year old boy who heard “Idiot Wind” coming through the tinny speaker of his black and white TV on the “Hard Rain” broadcast didn’t know a thing about Norman Raeben but he knew exactly what that beautiful man with the intense eyes in the white head-wrap was singing about. A powerful message from elsewhere about phony reality. Nothing beats that first take, when your whole life is at stake.

We’re idiots, babe

It’s a wonder we can even feed ourselves