Dylan Context

In Ecce Homo: How One Becomes What One Is, Friedrich Nietzsche declares: “One must pay dearly for immortality: one has to die several times while still alive” (660). Bob Dylan died and was reborn several times between his 1965 shows in Cincinnati and his 1978 return to the city. After an exhausting, combative, strung-out European tour in the spring of 1966, Dylan retreated to upstate New York for what was meant to be a brief hiatus before resuming his grueling concert schedule. Then he was injured in a motorcycle crash in July and abruptly canceled the rest of his tour. The relentless pace and debilitating habits of the road were unsustainable. During his convalescence, Dylan took stock and decided to refocus his priorities on raising a family. He had married Sara Lownds on November 22, 1965, just a couple weeks after his Cincinnati Music Hall show. They settled down in rural Woodstock and started filling their house with children.

Dylan took eight years off from touring, devoting himself to his new life as husband and father. He continued to make music, though his art was increasingly relegated to the backseat during the domestic years. His bandmates moved into a house nearby (nicknamed “Big Pink”), and the old gang would get together regularly for jam sessions in the basement. This music was never intended for release, but they did make demo tapes for use by other artists. The Band (formerly The Hawks) used a few songs from these sessions for their groundbreaking debut album Music from Big Pink (1968), and the group went on to have a hugely successful career independent of Dylan. Eventually bootlegs of other Big Pink songs began circulating among collectors, and Columbia finally released a selection years later called The Basement Tapes. During the post-crash period, Dylan also produced the sparse and ominous John Wesley Harding (1967). Over the next few years, he sporadically returned to the studio to lay down new tracks, including the albums Nashville Skyline (1969) and New Morning (1970), as well as a collection of covers titled Self Portrait (1970). By the early seventies, however, it seemed his creative fountainhead had dried up and he was drifting into artistic oblivion.

But never count Dylan out. He succeeded spectacularly in resurrecting his career in the mid-seventies. A key catalyst for this rejuvenation was his return to the stage. Unfortunately, his rebirth as a live performer coincided with the death of his marriage. When he left Columbia to sign with Asylum in 1974, the lucrative deal came with two strings attached: Dylan was expected to reunite with The Band for an album of new songs, and they were expected to promote the album on the road. The result was Planet Waves (1974)—Dylan’s first #1 album on the Billboard chart—supported by a sold-out stadium tour. Ticket sales were brisk, but album sales soon dropped off steeply, and by most accounts Dylan was disappointed with the detached concert experience of playing huge venues. Worse still, his marriage started to come unraveled.

Around the time he was splitting with his wife, he reunited with Columbia to produce Blood on the Tracks (1975), one of his strongest records ever and arguably the greatest breakup album of all time. Determined not to repeat the missteps of Tour ’74, Dylan put together a caravan of friends/troubadours and hit the road again, playing smaller venues in 1975 and 1976 on the legendary Rolling Thunder Revue. Dylan also put together one of his finest collections of story songs (most co-written with Jacques Levy) on Desire (1976). His marriage was over by the summer of 1977, but he was back on top as a live performer. Galvanized with renewed creativity, he embarked upon the longest tour of his career in 1978.

According to Paul Williams, “Dylan’s purpose in 1978 seems to have been to redo the ’74 tour (the great Bob Dylan retrospective) and do it right. He set out to play the songs that people wanted to hear—there were a significant number of greatest hits represented—but despite his entertainer stance he wasn’t interested in just granting his audience whatever they might wish from him” (Williams II 123). Dylan had played on crowded stages before, particularly on the Rolling Thunder Revue, but the 1978 tour was notably different. The large ensemble included saxophonist Steve Douglas, a member of the renowned Wrecking Crew who had played with the likes of The Beach Boys, Aretha Franklin, and Ike & Tina Turner. The lineup was heavy on percussion, too, with new drummer Ian Wallace accompanied by coveted conga player Bobbye Hall. Most notably, Dylan supplemented, amplified, and diversified the vocals by adding three talented backup singers. Carolyn Dennis, Jo Ann Harris, and Helena Springs (or The Queens of Rhythm as they came to be called) lent a soul/R&B/gospel element to live performances and cast foreshadows of even bigger changes ahead on the horizon.

The big band sound of 1978 was distinct from anything Dylan had tried before on stage. The experiment startled many listeners, including even some members of the band. Rob Stoner was the initial bass player for the tour. A veteran of the Rolling Thunder Revue, he recruited several members of the 1978 band and led them through extensive rehearsals before the tour kicked off in February. Stoner was skeptical of Dylan’s new approach. He speculated that Dylan “‘had in mind to do something like Elvis Presley, I think. That size band and the uniforms. He wasn’t very sure about it, which is why he opened way out of town. I mean, we didn’t go anyplace close to Europe or America forever, man, and I don’t blame him’” (qtd. Heylin 475). The tour opened in Japan, where a live album, Bob Dylan at Budokan, was recorded. Stoner found the results disappointing: “‘I think he knew, subconsciously, he was making a big mistake’” (qtd. Heylin 475).

Presley was very much on Dylan’s mind after the King of Rock ’n’ Roll’s untimely death the previous autumn. During the 1978 tour biographer Robert Shelton asked Dylan how he responded to Presley’s death. “‘I broke down,’” he admitted. “‘I went over my whole life. I went over my whole childhood. I didn’t talk to anyone for a week after Elvis died. If it wasn’t for Elvis and Hank Williams, I couldn’t be doing what I do today’” (qtd. Shelton 480). It seems fitting that Dylan replaced Stoner with Jerry Scheff, Presley’s long-time bassist. Scheff was headed for the first scheduled show of Presley’s new tour on August 16, 1977, when he learned of his boss’s death (Scheff 7-11).

Neil Diamond seems to have been the most direct influence on the look and sound of Dylan’s 1978 band. At the height of his fame in the late seventies, Diamond was sometimes called “the Jewish Elvis,” though the nickname was used as often in jest as in praise. “Many Dylan enthusiasts may find it difficult to accept as true the premise that Dylan was ‘borrowing’ from Diamond’s live show,” writes Derek Barker in the fanzine ISIS. “However, the first thing that doubters need to understand is just how big Neil Diamond was at that time” (222). Dylan and Diamond shared a manager, Jerry Weintraub, who was experienced at successfully coordinating large-scale tours like the one Dylan envisioned for 1978.

Dylan and Diamond had another close friend and collaborator in common: Robbie Robertson. Diamond had a remarkable run of three consecutive platinum-selling albums in 1976 and 1977, and two of them were produced by Robertson. Dylan fans delight in repeating the story about an alleged backstage clash with Diamond in 1976 at The Band’s final concert, The Last Waltz. As the story goes, Diamond left the stage after his performance and challenged Dylan: “Top that!” To which Dylan reportedly quipped: “By doing what? Falling asleep?” (Greene 2012). Within two years, however, Dylan was mounting stage spectacles cut from Diamond’s rhinestone cloth. “By the time Dylan’s 1978 tour went on the road, the comparison with Neil Diamond’s ‘shows’ was quite startling,” observes Barker. “Dylan’s big band set-up very much echoed the configuration of musicians that Diamond had used on his transitional album Beautiful Noise, which featured tenor sax and trumpet, keyboard, a separate percussionist (as well as a drummer) and three female backing vocalists” (223).

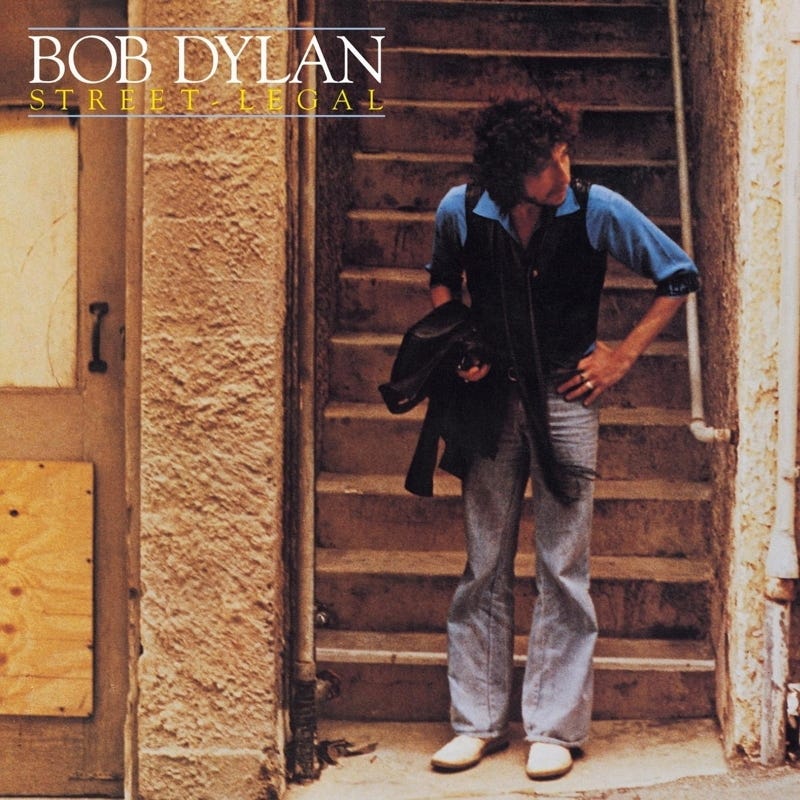

What mattered most wasn’t how the band looked but how it sounded. They may have stumbled tentatively out of the gate (though Budokan has some fierce defenders), but the general consensus is that they found their footing and built momentum over the course of 114 concerts in 1978. In the spring the group assembled to hastily record Street-Legal (1978). For listeners familiar with recording technology, this album is notoriously marred by sloppy production; for the rest of us ignorant about such matters, this fantastic collection of new songs can simply be enjoyed without reservation. The summer concerts were hailed as a triumphant tour de force in Europe, where Dylan had not played since 1966. Violin and mandolin player David Mansfield concedes that the tour sometimes gets a bad rap, but on balance he champions the high quality of the performances. “Beyond Budokan, there’s just audience tapes from later in the tour. Even on those, I can tell how amazing things got. It was a fantastic band. Every musician in that band was a total ace. It was the same with the singers” (Greene 2021). Mansfield credits Dylan as the spark igniting the band night after night. The kindling was a host of new musical arrangements for his older classics. As Mansfield puts it, “I love how he took the songs, twisted them up, and made them totally unique and different” (Greene 2021).

Fortunately, we’re in a position to judge for ourselves. A somewhat muffled but still audible recording survives from the October 15 concert at Riverfront Coliseum in Cincinnati. This bootleg (LB 07621) is my primary source. All quotations are transcribed from what Dylan actually sings in concert, which sometimes differs from the officially published lyrics.

Cincinnati Context

Cincinnati is a sports town. Dylan’s concert at Riverfront Coliseum placed him at the heart of the city’s sports world. The arena where he played is located right beside Riverfront Stadium, then home to the Cincinnati Bengals football team and the Cincinnati Reds baseball team. What a study in contrasts. The Sunday afternoon of Dylan’s concert, the winless Bengals (sometimes derisively called the Bungles) suffered their seventh straight loss to begin the 1978 season. At least the city had the Reds. In 1869 the Cincinnati Red Stockings formed the nation’s first professional baseball club, and the Reds had remained the most popular team in town for decades. The franchise was never better than in the 1970s. In that decade alone, the juggernaut nicknamed the Big Red Machine won six division titles, four league pennants, and back-to-back World Series championships in 1975 and 1976.

After the ’76 season, the Reds traded away first baseman Tony Pérez, nicknamed by fans “The Mayor of Riverfront.” The team slipped a step the following two seasons, finishing second in the division behind the rival Dodgers. The Reds concluded the ’78 season a couple weeks before Dylan’s concert and headed into one of the most fateful off-seasons in its history. In November the front office fired manager Sparky Anderson. In December the Reds’ most famous player, team captain and hometown hero Pete Rose, signed with the Philadelphia Phillies. The dismantling of the Big Red Machine was fully under way.

Riverfront Stadium opened downtown on the Ohio River in 1970, and Riverfront Coliseum opened beside it in 1975. A year after Dylan’s concert, Riverfront Coliseum would go down in infamy as the site of The Who tragedy.

On December 3, 1979, a large crowd assembled on a freezing night outside the locked arena, hoping to get the best spots possible at the general-admission concert by The Who. Mistaking a late sound-check for the beginning of the show, the crowd surged toward the first door that opened. During the ensuing stampede, 11 concertgoers, all aged 15 to 22, were trampled to death. A memorial plaque commemorating those who died now stands on the concourse outside the arena. But this horrific tragedy was still a year away.

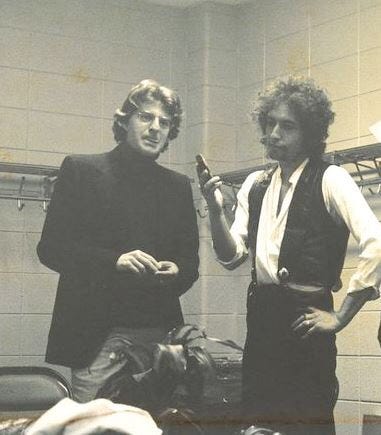

The mood at Riverfront Coliseum on October 15, 1978, was one of jubilation. It was concert #71 of the year for Dylan and the band, but for Cincinnati it was his first show in thirteen years and the hottest ticket in town. Jerry Springer was there. You don’t have to be from Cincinnati to be familiar with this colorful character. He would eventually become infamous as host of “The Jerry Springer Show” (1991-2018). Long before his “trash TV” show brought him national notoriety, Springer was a familiar figure on the Cincinnati political scene. He was elected to City Council in 1971 at the age of 27, but resigned in 1974 after getting busted for solicitation. It didn’t take Sherlock Holmes to solve the case, since he paid the prostitute with a personal check! But Springer was a survivor, ever since being born in a London Underground station during the Blitz. Only a year after resigning in disgrace, the charismatic young politico won back a seat on City Council, eventually serving as Mayor of Cincinnati (1977-1978).

Mayor Springer was a big Dylan fan and arranged to meet the star backstage to present him with the key to the city. He later recalled: “That’s how I got to meet all these celebrities I wanted to meet. I said, ‘If you come to Cincinnati and give us a concert, I’ll give you a key to the city.’ So in 1978 we had Dylan, we had Linda Ronstadt, Emmylou Harris, The Eagles, Kenny Rogers. I mean we had all these people coming in. It was just so I could meet them” (Springer). He wasn’t the only one eager to attend the sold-out show. When Dylan first played Cincinnati in 1965, he was booked at venues that could only fit 3,000 fans or less. When he returned in 1978, he filled Riverfront Coliseum to capacity at nearly 17,000. Dylan and his big band would give local fans their money’s worth, playing 27 songs that spanned his career and fundamentally reimagined some of his most beloved works.

The Concert

When: October 15, 1978

Where: Riverfront Coliseum

Band: Bob Dylan (vocals, guitar, and harmonica); Billy Cross (guitar); Carolyn Dennis (vocals); Steve Douglas (horns); Bobbye Hall (percussion); Jo Ann Harris (vocals); David Mansfield (violin and mandolin); Alan Pasqua (keyboards); Jerry Scheff (bass); Steven Soles (guitar and vocals); Helena Springs (vocals); Ian Wallace (drums).

Setlist:

1. “My Back Pages”

2. “I’m Ready”

3. “Is Your Love in Vain?”

4. “Shelter from the Storm”

5. “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue”

6. “Tangled Up in Blue”

7. “Ballad of a Thin Man”

8. “Maggie’s Farm”

9. “I Don’t Believe You (She Acts like We Never Have Met)”

10. “Like a Rolling Stone”

11. “I Shall Be Released”

12. “Going, Going, Gone”

*

13. “One of Us Must Know (Sooner or Later)”

14. “It Ain’t Me, Babe”

15. “Am I Your Stepchild?”

16. “One More Cup of Coffee”

17. “Blowin’ in the Wind”

18. “Girl from the North Country”

19. “Where Are You Tonight? (Journey through Dark Heat)”

20. “Masters of War”

21. “Just Like a Woman”

22. “Simple Twist of Fate”

23. “All Along the Watchtower”

24. “All I Really Want to Do”

25. “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m only Bleeding)”

26. “Forever Young”

*

27. “Changing of the Guards”

First Set

The concert opens with “My Back Pages.” Opens—not opened. As a literary scholar, I’m trained to write in present-tense verbs; but the historical orientation of this project constantly has me looking backward to previous eras where past-tense seems more appropriate. However, when responding to what I hear on the bootlegs, even when replaying recordings made decades ago, the experience feels present, as if unfolding, “again for the first time,” in the now. I’ll be including many clips from these bootlegs over the course of this Dylan in Cincinnati series, so you can also listen to these performances in your own present moment. The music comes out of the ether into your earbuds, and you receive it afresh right now. It’s a Play button, not a Played button. It’s a command: Play a song for me. At the end of the previous installment I suggested taking a trip in a time machine back to the past. But in another sense the trip moves in the opposite direction: we’re bringing it all back home, transporting the past into our present. So I’ll default to present-tense descriptions for concert commentary throughout Dylan in Cincinnati. It ain’t no use to sit and wonder why, dear reader, if you don’t know by now.

Rewind: The concert opens with “My Back Pages.” The song is played as an instrumental by the band, with no words and no Dylan. What a striking way to begin a concert by “the voice of his generation”—with an absent singer and a voiceless song. Even without supplying the lyrics for us, the audience already knows the familiar refrain: “Ah, but I was so much older then / I’m younger than that now.” Without saying it in so many words (or any words at all), Dylan announces that this show will not be a nostalgic trip back to the good old days. The night is young and so is the singer. This performance is not a return to the past. It is situated firmly in the here and now.

Dylan takes the stage during the final bars of “My Back Pages”—there’s no mistaking his entrance from the rapturous cheers—and launches into “I’m Ready.” Again, he seems intent upon defying expectations from the start. Here is the most legendary songwriter in popular music, yet he begins with a song written by Willie Dixon and popularized by Muddy Waters. According to Dylan’s website, he played “I’m Ready” in concert a total of 24 times, all between September and October 1978 (the final performance was five nights later in Richfield, Ohio). It’s probably only a happy accident that Dylan opens with a song by Muddy Waters, who just happens to be the first person ever to perform on the Riverfront Coliseum stage. Waters was the opening act for The Allman Brothers Band at the arena’s inaugural concert on September 9, 1975. Dylan surely selected “I’m Ready” for more theatrical reasons, as the song works perfectly as prologue for the evening’s performance.

With the music roaring behind them, Dylan and his fellow vocalists belt out:

I’m ready

As I can be

I’m ready

As I can be

I’m ready for you

I hope you’re ready for me

The song effectively sets the terms for the evening, inviting listeners into the experience and challenging us to keep up. This may not be the Dylan concert you were expecting, but it’s the one you’re going to get. Ready, set, go!

The “You” and “I” dynamic is endlessly fascinating in Dylan’s work and will come up many times over the course of this study. We might as well establish some bedrock principles right from the start by identifying signature features of the Dylanesque “You” and “I.” He writes lots of songs in the first-person voice (“I”) directed toward an addressee, sometimes specifically named, more often vaguely referred to as “You.” Readers must be thinking, “Yeah, sure, and so does every other songwriter.” Fair enough. But Dylan is unusually elastic in his use of these identity markers, adjusting them for different effects in shifting scenarios. Let’s start with “You.”

Dylan devotes considerable space in Chronicles to analyzing the Brecht/Weill song “Pirate Jenny.” In his early days in the Village, he sometimes tagged along with his girlfriend Suze Rotolo who worked at the Theatre de Lys. There he had the privilege of seeing Lotte Lenya on stage, and he describes being thunderstruck by her performance of “Pirate Jenny.” The song is about a hotel cleaning woman who plots revenge against “you gentlemen,” i.e., the rich, pampered, condescending, dismissive hotel patrons who casually mistreat her on a daily basis (think William Zanzinger). She must silently endure this degradation as a servant, but as her imaginary alter ego Pirate Jenny she vows revenge someday. In retrospect one can see the impact of “Pirate Jenny” on future Dylan compositions like “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll” and “When the Ship Comes In.” The song didn’t just influence him as a songwriter, however, but also as a live performer. Chronicles is less a straightforward memoir than an apprenticeship novel, basically Dylan’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. The people and events that make the cut into the book are those relevant to understanding his development as an artist. One of the most important lessons the young apprentice learned from the master Lotte Lenya was how to incorporate the audience into a song’s performance for unforgettable effect:

In the small theater when the performance reached its climactic end the entire audience was stunned, sat back and clutched their collective solar plexus. I knew why it did, too. The audience was the ‘gentlemen’ in the song. It was their beds that she was making up. It was their post office that she was sorting mail in, and it was their school she was teaching in. The piece left you flat on your back and it demanded to be taken seriously. (275, emphasis added)

As written, “you gentlemen” refers to the patrons of the hotel; but as performed, Lotte Lenya projected her rage straight at the audience, casting them as her adversaries and shooting threats like bullets through the fourth wall. Dylan frequently uses this performance technique in concert, treating the audience as the character being addressed. It is anyone’s guess who Willie Dixon had in mind when he wrote, “I’m ready for you / I hope you’re ready for me.” But when Bob Dylan sings it from the Riverfront stage, there is no doubt who is being addressed: each of the fans in attendance, and by extension, each of us bootleg listeners teleporting in from the future.

Who is “I”? This may sound like a dumb question with an obvious answer: I = Dylan. But it’s much more complicated than that. Consider the next song in the setlist, “Is Your Love in Vain?” This original composition had just been released on Street-Legal. According to Robert Shelton, “Street-Legal is one of Dylan’s most overtly autobiographical albums, telling of loss, searching, estrangement, and exile” (478).

By this logic, the “I” and “You” of the song would appear to be Bob and Sara Dylan: “All right, I’ll take a chance / I will fall in love with you.” Shelton’s reading jibes with popular references to the 1978 concerts as “The Alimony Tour,” as if Dylan’s globetrotting escapades were an elaborate midlife crisis, attempting to recoup his losses while also sowing his wild oats after years of marriage and a messy divorce. In performance, however, the singer’s interrogations are aimed squarely at the audience:

Do you love me?

Or are you just extending goodwill?

Do you need me half as bad as you say?Or are you just feeling guilt?

I’ve been burned beforeAnd I know the score

So you won’t hear me complain

Will I be able to count on you?

Or is your love in vain?

After the cocksure swagger of “I’m Ready,” the singer addresses listeners with less certainty and more vulnerability: I need you; I think you need me, too; but I’ve been betrayed (by audiences) before; so how do I know if I can open myself up and trust you? The “You” whose love is being tested is the listener. Does that make the inquisitor Dylan himself? Well, not exactly.

Identity is slippery in Dylan’s songs. Betsy Bowden tackles this problem head on in Performed Literature: “Let me pause to make an emphatic point. The narrator in the lyrics of a Dylan song may show some attitude toward women, toward war, toward authorities, toward whatever. But the ‘I’ in a song is not Bob Dylan. Like poems, songs can sometimes rework into artistic patterns the songwriter’s own experiences. But a song is absolutely not biographical evidence” (27).

I completely agree with Bowden’s assumptions, and so does Stephen Scobie. In Alias Bob Dylan: Revisited, he associates Dylan’s multiple personae with the trickster archetype: “The trickster’s play with identity is reflected, literally, in Dylan’s fondness for images of the self at one remove, the self which is itself but not quite itself—rather, identity as doubled, divided, or deferred. These images include alias, mask, mirror, shadow, brother, ghost, and all the echo-effects of allusion and quotation” (35). Dylan’s masks are most obvious in those rare cases where he overtly sings as a fictional character, as when he adopts the alias of a miner’s widow in “North Country Blues.” However, in practice the “I” narrator of most Dylan songs is an amalgamation of self and other, of truth and fiction. According to Scobie, “what Dylan will also do more subtly is to insert fictional details into apparently autobiographical texts. He thus problematizes any easy assumption of direct biographical reference and invites us to see the ‘I’ of his songs, always, as a persona, as a mask” (48).

I particularly like the way Timothy Hampton addresses this issue. He writes about Dylan’s multiple identities and creative detachment from any singular, essential, autobiographical self. In Bob Dylan’s Poetics: How the Songs Work, Hampton explains:

To study Dylan’s art and its combinatory power, we need to take into account the different ways in which he uses the ‘I’ who appears in his compositions. This ‘I’ is, of course, a fiction, just as the ‘I’ of Shakespeare’s sonnets is a fiction and the ‘I’ of Marty Robbins’s 1959 border ballad ‘El Paso’ is a fiction. It is a character that Dylan invents anew for each song. Sometimes that character knows many things. Sometimes it knows little. Sometimes it thinks it knows more than it does. Sometimes it says more than it knows. (18)

This fundamental distinction, between the hidden identity of the singer and the exposed identity of the song, may be what Dylan was getting at in Chronicles when he wrote: “Most of the other performers tried to put themselves across, rather than the song, but I didn’t care about doing that. With me, it was about putting the song across” (18). This passage might be read as a statement of humility and a prioritization of the song over the singer’s personal vanity. On another level, however, Dylan gestures toward something like T. S. Eliot’s depersonalization principle in “Tradition and the Individual Talent,” where art “is not the expression of personality, but an escape from personality.” As Eliot explains, “What happens is a continual surrender of himself as he is at the moment to something which is more valuable. The progress of an artist is a continual self-sacrifice, a continual extinction of personality” (Eliot). It’s about the song, not the singer. In Chronicles Dylan credits Arthur Rimbaud with teaching him a related lesson: “I came across one of his letters called ‘Je est un autre,’ which translates into ‘I is someone else.’ When I read those words the bells went off. It made perfect sense” (288).

Dylan compared his performance art to theatre in a 1978 interview with Philip Fleishman. Answering a question about the film Renaldo and Clara, Dylan spoke more broadly about his approach to playing characters: “Well, in any song I write or any movie I’m in, I always become the character in it. I play the character Renaldo in the movie. When I sing ‘It Ain’t Me, Babe,’ I’m another character. It’s all a play. My songs are closer to theatre than to ordinary rock and roll” (Fleishman, emphasis added). This notion of Dylan as an actor playing characters, and of his concerts as theatrical performances, is central to my study of Dylan in Cincinnati.

Too often, fans and critics of Dylan measure his effectiveness on a sliding scale of perceived sincerity and authenticity. On a good night he’s being real; on a bad night he’s being fake. There is a powerful temptation to equate the singer with the song, to believe that, when Dylan delivers a powerful performance, he is revealing his true self and real feelings to us. It’s a basic category mistake, but it has proven very difficult to resist, and I’m not sure why.

We don’t generally make this same mistake when watching great actors. I can easily suspend my disbelief when watching, say, Emma Thompson play Professor Vivian Bearing in Wit. I can sympathize with the character’s suffering to the point of sobbing every time I see the film—all the while knowing that after Mike Nichols yelled “Cut!” Thompson probably went back to her trailer, had a cup of tea, checked her messages, and visited the loo.

When it comes to Dylan, however, we’re apparently expected to believe that all the experiences and emotions he expresses are genuinely his own, because how else could he possibly put them across so convincingly otherwise? Rubbish. He’s a gifted actor, that’s how. This is a compliment, not an insult. Of course, he must draw upon a deep personal reservoir to feed his performance, as do all great actors: no one’s questioning that. But he’s also a seasoned player who has honed his craft for many years on stage, plying his trade as a public performer. It doesn’t make him a fraud—it makes him an artist. It’s about the song, not the singer.

Dylan is not only a shape-shifting actor, he is also a deliberate stage director. There is often a dramatic sensibility behind his setlists, and these design elements are on full display in his Riverfront concert. In part he strives for musical variety in selecting and ordering his songs. He told interviewer Robert Love that “it starts like this. What kind of song do I need to play in my show? What don’t I have? It always starts with what I don’t have. I need all kinds of songs—fast ones, slow ones, minor key, ballads, rumbas—and they all get juggled around during a live show. I’ve been trying for years to come up with songs that have the feeling of a Shakespearean drama, so I’m always starting with that” (Love). In addition, there are often shared images or thematic links connecting multiple songs together. Sometimes the juxtapositions are associational like collage. Other times there is a narrative trajectory, where individual songs function like scenes in a play, taking the listener through a dramatic experience with character conflict, plot complications, and varying degrees of resolution or irresolution.

“My Back Pages” and “I’m Ready” serve effectively as the opening prologue to Dylan’s Riverfront setlist. The next four songs cohere together as a narrative unit, a kind of first act, distilling down the entire lifespan of a relationship. “Is Your Love in Vain?” expresses the hesitant beginning of an affair, as the singer makes the decision to take a chance on a new love. He opens his heart to her, and she in turn opens her door to him, as described in the next song, “Shelter from the Storm.” As the refrain of the next song indicates, it all comes to an end in “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue.” However, the next song, “Tangled Up in Blue,” replaces the beginning-middle-end linear trajectory with a cyclical pattern of lovers who constantly oscillate between coming together and falling apart:

Split up on a dark sad night

Both agreeing it was best

She turned around to look at him

As he was walkin’ away

She said over her shoulder

‘We’re gonna meet again somedayOn the avenue’

Tangled up in blue

Just as she predicts, the singer and his soulmate keep alternating between breakups and reunions throughout the song. It’s never all over: the singer remains perpetually tangled up in Baby Blue.

The paragraph above summarizes the lyrical content and interrelations of songs, but this can only be fully apprehended in hindsight. The most immediate impact comes through the quality of performances, and, to be honest, they are quite uneven in the first set. If you’re reading Shadow Chasing, then you don’t need persuading that Dylan is an extraordinary performer. That said, if you’ve seen him in concert multiple times over the years, you probably also know that he’s more effective on some songs than others, on some nights than others, on some entire tours than others. The overall quality of the 1978 tour was up and down, and on any given night the mixed bag contained several gems but also some lumps of coal.

This wide range is on full display in the first set at Riverfront. “Is Your Love in Vain?” has the advantage of freshness. The song was first played at Budokan in February, appeared on Street-Legal in June, and after 31 performances was permanently retired in December 1978. Dylan’s new sound takes some getting used to, but there are things to admire here. The combination of organ with the holy harmonies of The Queens of Rhythm create a sonic atmosphere more sacred than seductive. It’s effective musically, but the weak link is Dylan’s lead vocal. He yelps more than sings most of the verses, leaning hard into a nasal whine as if doing an over-the-top Dylan impression.

The sound only deteriorates with “Shelter from the Storm.” Lyrically, the song looks back to a time when a woman took the singer in and offered him comfort and protection from life’s tempests. The new musical arrangement sounds like he’s back out in the storm—and it’s a clattering mess, like huddling through a hailstorm under a tin roof. All those additional instruments and backup vocals certainly increase the song’s volume, but at the expense of the intimate poignancy captured on Blood on the Tracks.

Fortunately, Dylan and the band lock into a more effective groove in their spirited “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue.” Despite the title’s announcement of an ending, this performance sounds like a new beginning. This is the first number where drummer Ian Wallace’s presence comes through forcefully, driving the beat behind a heart-thumping, head-bopping “Baby Blue.” The crowd especially loves it when Dylan breaks out his harmonica for an extended solo at the end. It sounds as if the band has finally found its way.

But then they become “Tangled Up in Blue.” Dylan has spoken about his attempt to defy time in writing this song, but here he seems hell-bent on a different kind of experiment with time, trying to see how long he can drag it out. The brisk 5½ minute pace from the album version is smeared down 8½ minutes of bloody tracks at Riverfront. It feels even longer. Dylan’s vocals fluctuate from belabored to bleating, and Alan Pasqua struggles unsuccessfully on keyboards to follow the singer’s lost meanderings. What a travesty of a great song.

Dylan concerts function like Rorschach tests for listeners. I suppose this is true for performance criticism in general. When it comes to Dylan, who has spent a career standing on stormy summits with a lightning rod in his fist, responses tend to be particularly charged. An individual’s reaction to Dylan in performance reveals at least as much about the listener as about the performer. What you hear is dictated by your conscious preferences and unconscious prejudices, by the psychological baggage you bring with you to the experience, and by innumerable factors largely outside your control, both external (e.g., the sound system, the temperature, who is seated beside you) and internal (e.g., the status of your personal relationships, job, health). Like all performers, Dylan is sometimes more “on” and other times comparatively “off.” To be fair, however, listeners are also more receptive to some performances than others. An honest reckoning in my own criticism demands a willingness to look both without and within, engaging in careful description as well as scrupulous self-reflection, explaining what I hear while also trying to account for why I respond positively or negatively, why I’m more open to some performances and closed to others.

Deciphering the inkblots of other critics can be easier. For instance, look at the sharply divided reactions to Dylan’s 1978 concert in the local press. Tom Brinkmoeller prepared the way for Sunday’s show with a profile on Dylan in the Thursday Enquirer.

Brinkmoeller played a game of limbo with his piece, setting the bar of expectations as low as it would go. He conceded Dylan’s legendary status from the sixties only to diminish his latest efforts as “gourmet bubblegum” (E-1). Even before Dylan arrived in town, Brinkmoeller was already belittling the concert as mere spectacle. He quoted Jim Fox, program director at WKRQ, who claimed, “‘People don’t go to hear Dylan music per se. They go because it’s an event. They go because they think the appearance just might be the last time he tours the country. They go not because they’re into his music but because he’s become a legend. It’s a hip thing to be at’” (E-1). It might be his last tour—in 1978!

Brinkmoeller wrote a hatchet job aimed at chopping Dylan down to size before he even performed. His colleague Cliff Radel actually bothered to attend the concert before writing about it, and his Enquirer review was as exuberant as Brinkmoeller’s was cynical. Radel extolled, “Bob Dylan was nothing short of magnificent during the concert’s 56-minute first half. He was in as fine a voice as he’s ever been and his ability to supercharge every song with emotion was without a doubt sharper than it has been at any point in his fabled career” (A-12). Radel’s counterpart at the Cincinnati Post attended the same performance and had a polar opposite reaction. In his review the next day, James Chute complained: “Whatever the reasons, Dylan does not seem to relish performing. Throughout much of Sunday night’s performance, he was aloof and distant” (19). Which is it? Bubble gum or magnificent? Supercharged or aloof? One band performed that night on the Riverfront stage, but it begins to seem there were as many concerts as there were listeners.

Dylan is frequently described as mercurial: always evolving, always changing and reaching and growing, never staying still in one place for long. An important challenge in listening to and writing about Dylan’s performance art is to be as open to change as he is. To put it plainly: some change is for the better, and some for the worse. Any criticism worth the name must retain the freedom and integrity to call out creative lapses as well as leaps forward. But being open to change also means being willing to alter your own perspective, to go back and revise your assessment if and when Dylan gradually convinces you that a performance works in a way that you initially resisted. I’ve had that experience many times while writing Dylan in Cincinnati. After repeated exposure to the 1978 bootleg, I’ve come to appreciate certain performances that underwhelmed me at first. An instructive example is “I Shall Be Released.”

When you’re hearing a song live and in person, you only get one shot: it’s in front of you, it’s happening now, and then it’s gone. If I only had my first impression to go on with this particular performance, then I would have been disappointed. Here are my original notes: “I want to like ‘I Shall Be Released,’ but it just feels too glitzed up to me. There’s a big sonic buildup, then some drum-infused bit, before Dylan and the other singers deliver the lines ‘I shall be released.’ The crowd seems to dig it, so apparently it does the trick for those in the room. But to my ears it sounds too show-bizzy, an affectation that disrupts Dylan’s connection with the song rather than enhancing it. After all, this song is about a lonely inmate longing to escape prison, one way or another, dead or alive. Maybe what I really miss is the piercing falsetto of Richard Manuel’s keening on The Basement Tapes.”

As I reread these notes, they still ring somewhat true to me. But they also come uncomfortably close to Michael Gray’s “How can this not disappoint?” harumph blasted by Lee Marshall (see the introductory Dylannati post). I wasn’t sufficiently receptive to this new performance because I was still clinging protectively to the version I first fell in love with. This is precisely what Dylan adamantly refuses to do when approaching his older songs. Cliff Radel did not need to hear the song multiple times to surrender his preconceptions and embrace the new arrangements. In his review published the very next day, he observed,

Dylan could have taken the easy way out and sung these numbers as he recorded them. He didn’t. Each song was sung to an extensively reworked melody. Dylan’s harmonic sense would put jazz greats to shame. The airs he produced from the original chord structures, and in the case of ‘I Shall Be Released’ a revamped one, were just as stimulating as the ones he immortalized on record. (Radel A-12)

He got it instantly. It took me a few tries, but I eventually caught up.

After returning to the bootleg many times and reconsidering my initial impressions, I’ve come to love the Riverfront performance of “I Shall Be Released.” Dylan really belts out the final verse with desperation, fully inhabiting the character of the prisoner and channeling his desperate yearning for escape. The gospel ambience provided by Carolyn Dennis, Jo Ann Harris, and Helena Springs strengthens his plea and gives it wings. This version of “I Shall Be Released” anticipates future Christian songs, musical sisters like “Pressing On” and “Solid Rock,” and lyrical brothers like “When You Gonna Wake Up?” [“You got innocent men in jail”] and “The Groom’s Still Waiting at the Altar” [“There’s a wall between you and what you want and you got to leap it”]. If we think of the singer as a Christian martyr, “I Shall Be Released” feels perfectly at home in a gospel setting. The prison he seeks to escape are the snares of temptation and the shackles of sin in this wicked world. He rises high above the walls that confine him, buoyed by inspirational music and lifted by angelic voices. I didn’t hear it at first. I hear it now.

Second Set & Encore

After cleverly playing themselves off with the song “Going, Going, Gone” (but they’ll be back!), Dylan and the band give the audience an intermission. They’ve played a dozen songs by this point, but they’re less than halfway through the setlist. Mirroring the opening of the concert, they begin the second set with a couple songs which serve as prologue for what’s to come in the form of direct addresses to the audience: “One of Us Must Know (Sooner or Later)” and “It Ain’t Me, Babe.” In his only Cincinnati performance ever of the song, Dylan lays out the crux of the conflict in the chorus:

Sooner or later, one of us must know

You were just doin’ what you’re supposed to do

Sooner or later, one of us must know

That I really did try to get close to you

When you’re sitting at home spinning Blonde on Blonde on your turntable, there is no doubt that the singer is aiming the song at an immature ex-lover. But when you’re attending live at Riverfront Coliseum, or vicariously joining the festivities by bootleg, then there’s equally no doubt that he’s singing just for you, describing the difficulty of maintaining his connection with the audience. Paradoxically, the performance succeeds in forging the very connection that the lyrics disavow.

The theme carries over into “It Ain’t Me, Babe.” “You” in the recurring line “You say you’re looking for someone” is us, the listeners. The singer insists that he cannot or will not deliver what needy listeners stuck in the past demand from him: “No, no, no, it ain’t me, babe / It ain’t me you’re lookin’ for, babe.” As if to underscore the point, this is the only solo acoustic performance of the concert. If you’ve come looking for a nostalgic reprise of folkie Dylan, then you’ve come to the wrong place and time. He’s younger (and more amplified) than that now.

The pull and push of contentious relationships become the dominant subject of this section of the concert. I held onto some doubts and resistance in the first set, but Dylan and company consistently win me over in the second half. The song that converts me, where I hop aboard like a Kings Island roller coaster and start unreservedly enjoying the ride, is “One More Cup of Coffee (Valley Below).” It sounds remarkably different here than on Desire or the Rolling Thunder Revue or Budokan. This performance is much faster and harder, and the pronounced drumbeat, the sax, and the backing vocals add significantly to the frenzy. On the album the singer sounds like he is wandering alone away from the campfire and into the gloaming. In the Riverfront version, he sounds like Custer charging with his cavalry into the doomed Battle of Little Bighorn.

At its worst, the big band can sound cacophonous, as it sometimes did in the first set; but at its best, as on “One More Cup of Coffee,” the musicians all play together with a common purpose, summoning a thundercloud to the bursting point. Dylan is the head storm-chaser, and the band howls behind him at gale force. I hear Lear on the heath: “Blow winds and crack your cheeks! Rage! Blow!” (Shakespeare 3.2.1). This is the highest intensity level of the evening by far, and though it barely resembles other superb renditions of the song I’m accustomed to, it totally works. Locals will get this reference—it’s like Cincinnati-style chili: the first key to liking it is not expecting it to taste like chili.

As the second set progresses, the song selection seems guided less by lyrical or narrative themes and more by musical variety and striking aural contrasts. The squall line of “One More Cup of Coffee” is succeeded by the refreshing breeze of “Blowin’ in the Wind.” Dylan sang his most beloved anthem countless times before this night, including every show on the 1978 tour. But repetition does not result in apathy. He sounds locked in and fully committed to the song. He reconnects for the thousandth time with his wellspring of inspiration and pours out a poignant, stately performance, played beautifully in tandem with pianist Alan Pasqua, and gorgeously accompanied in the refrain by The Queens of Rhythm.

With the audience securely in the palm of his hand, he treats us to another favorite with “Girl from the North Country.” I hear echoes of “Spanish Is the Loving Tongue,” one of Dylan’s best-loved covers, in this lovely Riverfront performance. As a bandleader, he has expert instincts about when to hit the accelerator and when to tap the breaks. Having revved up the musical engine with a smoking “Coffee,” he cannot keep burning that hot without flaming out. So he cools off for a couple of songs, lowering the temperature and slowing the pace, before sending the show hurtling again full throttle into steamy darkness.

Enter “Where Are You Tonight? (Journey through Dark Heat).” This scorcher is the album closer on Street-Legal, and tonight’s rendition is only the seventh time he ever performed the song live. Frankly, it sounds a bit rough, like the band isn’t as sure of itself as it had been on the previous few songs. Musically, “Where Are You Tonight?” does at least succeed in accelerating the pace, though the tempo drags compared to the superior album performance.

Lyrically, the song makes an interesting choice to follow “Girl from the North Country.” The quiet 1963 ballad is a tender supplication to a distant (deceased?) lover who is invoked with reverence. Things have gotten more ambivalent and sordid by 1978, where the singer finds himself torn between faith and lust, spirit and flesh. This Everyman is drawn upward by an idealized holy woman hovering among the stars, but he is also tugged downward by a seductress working the pole at a seedy strip joint. If this sounds to you like a raging Madonna/Whore Complex, then you’re hearing it the same way I am. The singer reportedly survives his dark night of the soul by song’s end, but one suspects that when the sun next sets he’ll run the gauntlet all over again through dark heat.

In previous installments on March and November 1965, I pointed out some gender biases in 1965 local media coverage of Dylan. You might have expected some progress on this front in the thirteen years since he last visited the city, but in some ways the prejudice was even more pronounced in 1978. Take for example the Enquirer’s Cliff Radel. I acknowledge the journalist above for being better attuned to Dylan’s innovations than I initially was. But when it comes to the women in Dylan’s life and music, he was gallingly close-minded and tone-deaf.

It starts with the title of his concert review: “Thanks to the Mrs., Bob Dylan Turns Adversity into Triumph.” Confused? Let Radel explain:

Thank you, Sara Dylan. If it wasn’t for you wanting a divorce, your husband, Bob, might still be sitting in that mansion he built overlooking the Pacific. What with legal fees and alimony checks looming over his head, that was not to be. He had to go out and work. And work for Bob Dylan means writing songs, recording them and going out on tour. Thanks to you, Sara Dylan, he had to do all this. The results were the superb album Street-Legal and a tour which stopped at Riverfront Coliseum Sunday evening. Without you, Sara Dylan, the 16,940 fans who filled the arena would have been cheated. They would have missed the tremendous concert your ex-husband gave. (A-12)

Wow. I am struggling to find non-expletives to express my contempt for Radel’s unprovoked attack on Sara Dylan as a means of raising Bob Dylan on the carcass of his vanquished marriage. What an outrageously distorted view of Dylan’s art, and what a mean-spirited, completely unjustified dig at Sara Dylan. Praise the music, fine. Applaud the performance, and I’m right there with you. But why take needless cheap shots at the man’s ex-wife in the process?

Radel’s unprovoked digs don’t end with Sara Dylan. While heaping praise on Dylan’s performance, he slings something else on the women singing beside him: “Throwing a damper on all the great music on stage, including the sounds produced by the tight eight-member band, were three useless backup singers, Carolyn Dennis, Jo Ann Harris and Helena Springs. These vocalists simply could not keep up with their boss. Dylan has too variable a voice, too expressive and too imaginative to be forced to sing in unison with anyone” (A-12). Three useless backup singers? Like any listener, Radel is free to his musical tastes. But his repeated belittling remarks toward women in this review make it clear that we’re dealing with more than just aesthetic criticism. Radel flippantly flashes his misogyny as if it were a badge of honor. Elsewhere he offers legitimately keen insights into Dylan’s performance, and I’ll give him credit where it’s due. However, I’ll also call him out when he deserves it for sexist bullshit like this.

Truth be told, Dylan has been accused of sexism at times, too. I mentioned the Madonna/Whore dynamic of “Where Are You Tonight?,” so I should also point out the embarrassingly retrograde sentiments of an earlier song in the setlist, “Is Your Love in Vain?”:

Can you cook and sew?

Make flowers grow?

Do you understand my pain?

Are you willing to risk it all?

Or is your love in vain?

[Insert cringe here.] I’ve emphasized that Dylan sings in character, even when that character goes only by the name “I,” so we shouldn’t necessarily equate the views expressed in the song with those of Dylan himself. It’s hard to give him a pass, however, when it comes to comments delivered on stage between songs. Late in the concert, when introducing the band, Dylan resorts to a shtick he used throughout much of 1978: “On backup vocals tonight, my ex-girlfriend on the right, Jo Ann Harris. That’s right. On the other side, my new girlfriend, my current girlfriend, Carolyn Dennis. And in the middle my fiancée, Miss Helena Springs.”

I guess this is intended as harmless vaudevillian humor. Is it though? The Queens of Rhythm were routinely targeted for ridicule. Radel’s snub about “three useless backup singers” remains a view widely held among Dylan snobs. The supporting vocalists could have used some vocal support from their bandleader in 1978. Instead, he tells a promiscuous joke that reinforces the slander that these women were on tour more for their performances off stage than on it.

When it comes to charges of sexism, the song usually listed at the top of the indictment is “Just Like a Woman.” It’s the twentieth song Dylan sings at Riverfront, and the crowd gobbles it up. The lead vocal sounds to me like the winning contestant at Dylan Karaoke Night. He over-accentuates his oft-imitated vocal idiosyncrasies to the point of self-parody. But, just like a karaoke crowd, the Cincinnati fans are there to party, not to judge, and they audibly have fun with this performance. “Just Like a Woman” sounds much better if you don’t pay very close attention to the words:

She takes just like a woman, yes, she does

She makes love just like a woman, yes, she does

And she aches just like a woman

But she breaks just like a little girl

Marion Meade famously skewered these lyrics in her 1971 New York Times article “Does Rock Degrade Women?”: “There’s no more complete catalogue of sexist slurs than Dylan’s ‘Just Like a Woman,’ in which he defines woman’s natural traits as greed, hypocrisy, whining, and hysteria. But isn’t that cute, he concludes, because it’s ‘just like a woman.’ For a finale he throws in the patronizing observation that adult women have a way of breaking ‘just like a little girl’” (D-13).

It is tough to exonerate the song completely from these charges. But as usual with Dylan, it’s less straightforward and more complicated than it appears at first, as feminist critics from Ellen Willis and Betsy Bowden to Pamela Thurschwell and Laura Tenschert have taught me. Writing as a contemporary of Dylan, Bowden claimed she was never offended by the song, but rather shared its rejection of outdated expectations for feminine behavior. She asserted, “My point is that in spite of vicious attitudes toward women in the printed lyrics of Dylan’s nonlove songs, those songs were helping me subconsciously articulate what kind of a woman I did not want to be. Listening over and over, it never occurred to me to identify or even sympathize with the beribboned and curly-headed Baby being rejected by such a song’s narrator” (Bowden 54).

Writing four decades later, Tenschert believes the song opens a revealing window into pressures faced by women of an earlier era. As a fourth-wave feminist, she recognizes gender as a socially constructed performance, and she hears that dynamic acted out in the song:

To me, the song is about femininity—and more precisely, about the performance of femininity. What I mean by that, as we grow up, we learn, through how we’re raised and shaped by family, peers, and society as a whole, what it means to be a man and what it means to be a woman. And these understandings of gender roles—what a man or a woman was supposed to be like, what they were supposed to act like—were a lot more rigid and narrow in the sixties. […] The woman described behaves ‘just like a woman’ is expected to behave. The way she dresses and is made up to look attractive. And yes, in the way she interacts with a man: ‘she takes,’ ‘she makes love,’ ‘she aches’ according to her role, as long as she is moderately in control. It is only when ‘she breaks’—that is, when she loses control over her performance—that she falls back into being ‘like a little girl,’ without the learned guidelines of how a woman should act.

I quote Tenschert at length, not just because I think this is a really insightful interpretation, but especially because of her focus on performance. When it comes to performance criticism of Dylan, there is no separating what he says from how he says it and how the musicians perform it. If we’re considering gender performance as it relates to the 1978 Riverfront “Just Like a Woman,” we should notice that the male voice is outnumbered three to one by women’s voices. Here the so-called Baby is not simply being judged by a disapproving man, but also by a female jury of her peers. The song is flexible enough to accommodate diverse interpretive approaches, both critical and performative. The singers slip in and out of guises, and so do the listeners.

Rounding third and heading for home, Dylan and the band give it their all with three “All” songs in a row: “All Along the Watchtower,” “All I Really Want to Do,” and “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding).” “Watchtower” is Dylan’s favorite song to play live, with 2,268 concert performances according to his website’s count. On this particular night the band absolutely shreds it.

This song makes a believer out of the sanguine Post critic James Chute. After characterizing the first 21 songs as aloof and detached, Chute has an epiphany with “Watchtower” and witnesses the concert’s resurrection:

But never give up on Dylan. Count him dead, and he’ll always be back. Song number 22 is ‘All Along the Watchtower.’ The band, which was professional but bored all evening suddenly came alive. David Mansfield plays an electrifying violin solo. Guitarist Billy Cross steams the frets right off the guitar, and sax-player Steve Douglas wails away, sounding something like King Curtis on a good evening. Mansfield ends the song with an incredible cadenza, and the crowd was on its feet—for the first time since Dylan came on the stage almost two hours earlier. (19)

The wave of hard-rocking exhilaration even sweeps up one of Dylan’s finest acoustic songs, “It’s Alright, Ma.” I’ll admit to resisting this performance at first. I regard this song as such a lyrical masterpiece, and I so admire Dylan’s piercing and perfectly enunciated acoustic performances from 1965, that at first I only notice what is lost in drowning out the words with so much noise. Where’s Pete Seeger’s ax when I need it! It’s easy to pile on to those who booed Dylan back in the mid-sixties, mocking their cluelessness and dogmatism, secure in the knowledge that we would never have made the same mistake. But the truth is that a fundamental part of being a Dylan devotee is sometimes reacting against his latest move, preferring an earlier version or voice or song selection or musical arrangement. We’re not always wrong: there are such things as bad Dylan performances and poor (or at least comparatively subpar) artistic choices on his part. His instincts are right a remarkably high percentage of the time, however, even when not immediately apparent. As I’ll keep stressing, an honest performance criticism must include moments where Dylan lost me as a listener but then won me back.

In the present case, I re-listened to “It’s Alright, Ma” and tried to imagine what someone who had never heard the song before might hear. First, they’d register that this supercharged version totally rocks. Dylan is so invigorated that you wish he had arrived at Riverfront earlier in the day and suited up for the Bengals. The Cincinnati performance blows the socks off the Budokan performance recorded early in the tour. Writing about “It’s Alright, Ma” in his chapter on Bringing It All Back Home, Paul Williams observed, “Ironically, this song, which Dylan performs unaccompanied on the ‘folk side’ of his half-folk, half-electric fifth album, is more of a rock and roll performance than anything else on the record, and owes its success to basic rock and roll techniques and values: penetrate with the rhythm and the sound, and let them start hearing the words after they’re already hooked on the way the song feels” (Williams I 132). Considered from this perspective, perhaps the rockified Riverfront arrangement recovers something dormant lying within the song from its inception. Furthermore, as Williams observed of the ’78 tour in general,

The songs had new arrangements because he believed in them as living creations, he was celebrating their elasticity and universality, and he also was insisting that he be allowed to sing them as the person he was at the moment. It wasn’t so much that the new arrangements were more representative of who he was now than the old ones—it was that he had had to consciously strip the songs of their nostalgic value in order to be able to freely perform them as a singer, a living artist, rather than as some kind of phonograph. (Williams II 123)

The more I listen to the new arrangement of “It’s Alright,” the more I’m convinced that it is all right. I once was lost, but now I’m found; was deaf, but now I hear.

Dylan closes the second set with “Forever Young,” another song that comes across in performance as a message delivered across the footlights directly to the audience. He begins the first set with the promise of youthful rejuvenation [“I was so much older then / I’m younger than that now”], and comes full circle at the end of the second set with a closing prayer for perpetual youth [“May you stay forever young”]. It’s a powerful performance, far superior in my opinion to the one captured on film in The Last Waltz.

Listening to the bootleg, you can hear a surge of cheering after Dylan has finished singing but before the band stops playing. I assumed this was a grateful farewell from the audience as their hero exited the stage, but then I read Chute’s review and discovered what really happened: “A hand-lettered poster with a giant peace-sign read ‘Dylan is Hip—only the date has changed.’ Dylan liked it, and in a rare gesture, he plucked the poster out of the audience and handed it backstage” (19).

The final song of the Riverfront concert is a blistering encore performance of “Changing of the Guards,” the opener for Street-Legal and the closer for most of the fall 1978 concerts. The singer boldly declares, “But Eden is burning, either brace yourself for elimination / Or else your hearts must have the courage for the changing of the guards.” In retrospect, this announcement of an existential crisis and moral turning point seems prophetic.

About a month after the Cincinnati show, Dylan was playing in San Diego when another audience member reached across the divide to give him something—not a poster this time but a silver cross. He recalls,

Towards the end of the show someone out in the crowd . . . knew I wasn’t feeling too well. I think they could see that. And they threw a silver cross on the stage. Now usually I don’t pick things up in front of the stage . . . But I looked down at that cross. I said, ‘I gotta pick that up.’ So I picked up the cross and I put it in my pocket . . . And I brought it backstage and I brought it with me to the next town, which was out in Arizona . . . I was feeling even worse than I’d felt when I was in San Diego. I said, ‘Well, I need something tonight.’ I didn’t know what it was. I was used to all kinds of things. I said, ‘I need something tonight that I didn’t have before.’ And I looked in my pocket and I had this cross. (qtd. Heylin 491)

On November 19, 1978, Dylan claims he was visited by Jesus in his hotel room in Tucson, Arizona, and there he accepted Christ into his heart as his Lord and Savior. This new chapter of his life, and soon his art, was in many ways even more radical and controversial than going electric in 1965, and going religious likewise provoked backlash from fans who felt stunned and betrayed.

We’ll have to wait until the next installment of Dylan in Cincinnati to encounter the Christian troubadour on his next trip to town in 1981. As for 1978, Dylan proved himself adept once again at combating audience resistance and making converts out of skeptics. As I hope this extensive reflection on the concert demonstrates, he certainly made a believer out of me.

Works Cited

Barker, Derek. “1978 and All That.” Bob Dylan Anthology, Volume 2: 20 Years of Isis. Ed. Derek Barker. Chrome Dreams, 2005.

Bowden, Betsy. Performed Literature: Words and Music by Bob Dylan (2nd ed.). University Press of America, 2001.

Brinkmoeller, Tom. “For the Dylans They Are A’Changin’.” Cincinnati Enquirer (12 October 1978), p. E-1.

Chute, James. “Change on Change.” Cincinnati Post (16 October 1978), p. 19.

Dylan, Bob. Chronicles, Volume One. Simon & Schuster, 2004.

---. Official Lyrics to Dylan Songs. The Official Bob Dylan Website,

http://www.bobdylan.com/.

Eliot, T. S. “Tradition and the Individual Talent.” Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/69400/tradition-and-the-individual-talent.

Fleishman, Philip. “With Bob Dylan.” Maclean’s (20 March 1978), https://archive.macleans.ca/article/1978/3/20/with-bob-dylan.

Greene, Andy. “Flashback: Neil Diamond Proves Himself Worthy at ‘The Last Waltz.” Rolling Stone (16 October 2012), https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/flashback-neil-diamond-proves-himself-worthy-at-the-last-waltz-57931/.

---. “David Mansfield on His Years with Bob Dylan, Bruce Hornsby, Johnny Cash, and Sting.” Rolling Stone (27 January 2021), https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-features/david-mansfield-interview-bob-dylan-rolling-thunder-revue-1118794/.

Heylin, Clinton. Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades Revisited. William Morrow, 2001.

Hampton, Timothy. Bob Dylan’s Poetics: How the Songs Work. Zone Books, 2019.

LB 07621. Bootleg Recording. Taper Unknown. Riverfront Coliseum, Cincinnati (15 October 1978).

Love, Robert. “‘Passion is a young man’s game, older people gotta be wise.” The Independent (7 February 2015), https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/music/features/bob-dylan-interview-passion-is-a-young-mans-game-older-people-gotta-be-wise-10029328.html.

Meade, Marion. “Does Rock Degrade Women?” New York Times (14 March 1971), p. D-13.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. Ecce Home: How to Become What One Is. The Portable Nietzsche. Ed. and trans. Walter Kaufmann. Viking, 1954.

Radel, Cliff. “Thanks to the Mrs., Bob Dylan Turns Adversity into Triumph.” Cincinnati Enquirer (16 October 1978), p. A-12.

Scheff, Jerry. Way Down: Playing Bass with Elvis, Dylan, The Doors & More. Backbeat, 2012.

Scobie, Stephen. Alias Bob Dylan: Revisited. Red Deer Press, 2003.

Shakespeare, William. King Lear. Arden Shakespeare Third Series. Ed. R. A. Foakes, Methuen, 1997.

Shelton, Robert. No Direction Home: The Life and Music of Bob Dylan. Beech Tree Books, 1986.

Springer, Jerry. “Episode 80: Meeting Bob Dylan.” The Jerry Springer Project: Tales, Tunes, and Tomfoolery (1 November 2016), https://shows.acast.com/5bd89a1be7394b07090e2d64/episodes/meeting-bob-dylan-ep-80.

Tenschert, Laura. “Episode 9: Women and Dylan.” Definitely Dylan (11 March 2018), https://www.definitelydylan.com/listen/2018/3/11/episode-9-women-and-dylan.

Williams, Paul. Bob Dylan, Performing Artist, 1960-1973: The Early Years. Omnibus, 2004

---. Bob Dylan, Performing Artist, 1974-1986: The Middle Years. Omnibus, 2004.

Beautiful. Around our house we speak Dylan fluently.

I saw Dylan a couple of weeks before you, on September 26,1978, in Springfield, Massachusetts. What a great nostalgic experience your post is! It was a fantastic year for concerts; I remember seeing Linda Ronstadt, Jackson Browne, and Crosby, Stills and Nash in a one week time frame. Why your nearly two year old post appeared in my feed is a mystery. Thank you. By the way, I saved nearly all my old ticket stubs from back in the day. This concert set me back a whopping ten bucks!